Synchronous Meetings Overview

By Stacey M Johnson, Assistant Director for Educational Technology, Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching

Cite this guide: Johnson, S.M. (2020). Synchronous Meetings Overview. Vanderbilt University Course Development Resources. https://www.vanderbilt.edu/cdr/module-2/synchronous-meetings/

If you choose to include a live, synchronous component in your online course, you may have questions about how to set the stage for student success. Here are some answers to commonly asked questions about effective synchronous class meetings. For the purposes of this discussion, synchronous meetings are conducted using live video conferencing software, which at Vanderbilt is Zoom. Instructors can find help using Zoom here and here.

Should I just move my entire f2f lesson plan to a video conference?

Probably not. Video conferencing does not have all the same affordances as being in a physical space together. A thoughtful mix of synchronous and asynchronous learning activities is generally more effective than simply reproducing f2f plans via Zoom.

When planning which online activities to do synchronously and which to do asynchronously, it can be useful to divide up classroom learning activities into two general categories: presentational and interactional. Presentational activities are things like lecture, student presentations or performances, or other one-way communication. One person or group is doing all the communicating and the other person or group is taking it in. Interactional activities require everyone to be actively involved in real time. Live, synchronous interactions might include group discussions perhaps using techniques like fishbowl or breakout rooms, polling, or Q&A sessions. You can learn more about these kinds of discussion techniques in the next section.

One of the most helpful things you can do for making good use of video conference time is to identify and tease apart which parts of your f2f practice are presentation and what parts are interaction—a conscious uncoupling, if you will. All instructors, no matter their teaching style, do a little of both just in different proportions. Consider including mostly interactional activities on Zoom. You can structure your class so the presentational elements are asynchronous learning activities that take place before students come to the Zoom meeting. For example, you can extract the lecture portions of your lesson plan and turn those into asynchronous videos for students to watch before the meeting. Then, your video conference can be focused on the parts of your f2f class that are interactional.

How long should a synchronous class session be?

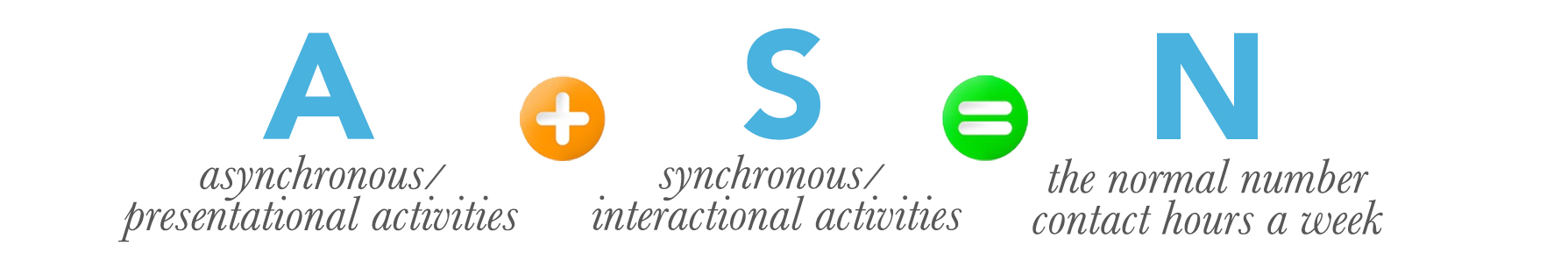

There is no definitive answer for this question, but if you have found yourself in Zoom meeting after Zoom meeting for the last few months, you might say the shorter and more focused the video conference, the better. Video conferencing can be exhausting. If you follow the advice above to focus your video conferencing on interactional activities, your synchronous class meetings will be shorter than your usual f2f class time. The math for virtual contact hours should be:

Different online faculty have different ideas about the ideal mix of f2f, synchronous, and asynchronous learning activities. My own personal metric for teaching in a hybrid (part f2f, part online) format is that the f2f portion of class is no more than 1/4 of the total weekly contact hours, and that we use that time for activities that just aren’t as effective or as efficient asynchronously. Here at the Vanderbilt Center for Teaching, that is also the metric we used in designing our online workshops. That includes the Online Course Design Institute with 3 hours asynchronous work per day and 1 hour of synchronous time for peer feedback and Q&A sessions. As you teach online and develop a sense for your own process, your ideal mix of f2f, synchronous, and asynchronous activities will inevitably vary.

How can I ensure that the synchronous and asynchronous parts of my class work together?

Students will notice if the activities in the two modalities feel disconnected. Crafting synchronous and asynchronous learning activities that inform each other helps to create a cohesive, logical learning experience for your students. Here are some strategies for strengthening those connections.

- Start with a module structure that clearly articulates how asynchronous and synchronous activities inform each other

It’s hard to explain to students how the different elements of the course are connected if you haven’t mapped that out for yourself first. Part 1 of this site has detailed guidance on how to structure modules and well as examples of different approaches. Starting with a consistent structure will help, but you may also need to think through where the connections are and how you will help students recognize the overall learning plan. Sharing your module structure, learning objectives, and other design considerations with students, perhaps in the syllabus, will help students see what you already know: that your course has been designed with their learning in mind.

- Explicitly point out connections between synchronous and asynchronous activities

Give students assignments to complete before the synchronous meeting that will help them be prepared, and mention how the activity will help. During the video conference, remind students of the work they did that is relevant to the current discussion. Occasionally and briefly pointing out connections is an easy, helpful step.

- Begin synchronous meetings by sharing discussion board posts or annotations relevant to the current meeting

Highlighting student contributions to asynchronous activities has several benefits in addition to connecting modalities. One benefit is that you are providing the whole class positive examples of successful student work. How will students in your classes know what kinds of posts you want during asynchronous engagement unless you show them examples? Another benefit is the motivation that results from positive reinforcement. Holding up specific student posts as positive examples shines a light on those students and allows them to feel successful, valued, and seen in your course.

A word of warning about highlighting specific student work. These practices can also go wrong. If you highlight the same students or students with specific identities over and over at the expense of the rest of the class or if you single students out as negative examples, this practice can be demoralizing and marginalizing. You might consider keeping a list of who you highlight and when you mention them to ensure that you are not falling prey to implicit bias, but rather are seeking out good work to highlight from every student at some point in the semester.

How can I get my students to engage more in synchronous meetings?

There are many strategies you might use, many of which are the same as strategies you might use in a f2f classroom. Others are specific to video conferencing. For example, if you are lecturing over video conference and are not sure if your students are tracking, you have options. You can:

- Go asynchronous and record your lecture as a video. Then use a video annotation tool to have students actively engage with the asynchronous video. See this page for video annotation tools options, and this page for developing asynchronous interaction with content.

- During the lecture, set up a simultaneous online chat so students can add to an ongoing backchannel while they listen. You might even assign a handful of students to be the backchannel moderators. The moderators’ job would be to ask questions, engage with classmates, and to speak for the class when the instructor stops to ask for questions. Video conferencing software like Zoom comes with a built-in chat tool, but your course management system likely has one as well, or you can use a discussion tool like Slack or Teams.

- Rather than simply counting on students coming to class discussions with something to contribute, help them along by organizing structured discussions. More on structured synchronous discussion techniques on the next page.

- Write a clear agenda for the meeting that students see in advance to give them time to prepare their contributions. Furthermore, consider asking students to prepare for the meeting ahead of time as part of their asynchronous learning activities. Giving students specific information about what will be expected and then building in time for them to prepare is a recipe for success.

Can I set policies for mandatory synchronous attendance or behavior during meetings?

In an ideal world, all of your students would show up to the synchronous sessions feeling excited to learn and ready to contribute. However, for reasons outside of their control, that might not always be the case. Forcing students into complying with certain video conferencing policies might seem like a shortcut to engagement, but can also cause more harm than good. Carefully consider how much grace you are able to show your students, and set policies that balance your own teaching preferences with student realities. Here are a few examples that may require careful attention.

- Attendance

What will happen if students are unable to attend the synchronous sessions? Perhaps because of time zone issues, technology limitations, or health reasons, you may find that you have absences that are not covered in your typical f2f attendance policy. Consider if it will be possible to provide other ways for students to engage in the interactional activities if they are prevented from attending a synchronous meeting. Perhaps you could record the meeting and give students access via a video annotation tool, or ask students in the meeting to take collaborative notes that can be shared with everyone, then assigning the student who missed the meetings to read the notes and ask questions on the discussion boards. With some creativity, everyone can be involved in class, even if they cannot be there synchronously.

- Camera and mic muting

It can be disconcerting to look at your computer screen and see a wall of black squares because most of your students have muted their cameras. One way to mitigate this is to require students to keep their cameras on during class. I would urge you to consider carefully what and how much camera and mic use to require of students in synchronous meetings. This post from Funmi Amobi at the University of Oregon may be helpful in making your decisions.

The same goes with mic muting. There are good reasons students may or may not want you to hear their background noise during a synchronous session. Allowing students to choose whether they type or talk is the most respectful choice.

As the instructor, you should make your preferences and hopes for your synchronous class time very clear to students, and also think about how you can give students agency to engage in the ways that meet their needs as learners, rather than centering your experience as the instructor.

- Other online conduct policies

You may have read Zoom etiquette articles that give all sorts of advice about how to engage in video conferencing. No eating! No taking calls in your bedroom! No cats on the keyboard! No children interrupting to ask for help with their homework! Such policies are put into place to enhance the experience for everyone, but they can also have unintended consequences.

Before instituting any of these policies, I want to carefully weigh why they are important and what effect they may have on my classroom climate. If a student is in back-to-back Zoom calls from 9am to 2pm and mine is the last of their day, what effect will it have to forbid eating? Will they be so hungry during class they cannot focus? Will they just turn off their camera so no one has to watch them eat? What does it communicate to the student that I am policing how they eat in their own home? Thinking deeply about the intent and possible unintended consequences of my policies can help me craft more effective guidelines for students.

Policies for synchronous learning are generally meant to ensure that students stay engaged during learning. But a top-down policy for Zoom conduct might not be the most effective approach. Well structured, interactive video conferencing meetings that ensure student engagement are a better way to get everyone into the video conference ready to learn. On that note, Karen Costa wrote this insightful piece about different ways to engage students in Zoom meetings without requiring cameras on.

Should I record my synchronous video conference and make it available to students who couldn’t be there?

This is another question without a one-size-fits-all answer. My own preference is to record presentational learning activities, but not to record interactive discussions. I think recording is less useful for interactive learning. My reasons are twofold. First, there are so many useful kinds of asynchronous interactions available to us as instructors. Taking advantage of such tools is much more straightforward than recording and making videos available to some or all of my students. Second, sitting through long hours of video conferences is hard enough, but watching recordings of other people’s meetings sounds, to be perfectly frank, extremely boring. I just don’t have it in me to watch such recordings, and I don’t expect my students do either.

Cynthia Brame, Associate Director of the Vanderbilt Center for Teaching, in a recent blog post provided four categories of questions that faculty should ask themselves before deciding whether recording their synchronous sessions is the right decision.

1. Questions about the goals of the session

-Is content delivery a goal of the session?

-Is student exploration and application of content the major goal of the session?

2. Questions about the role of community and discussion in knowledge building

-Does the session rely on active discussion among the students?

-Does the discussion rely on a feeling of community among the students?

-Does recording change students’ willingness to attend or to actively contribute?

3. Questions about the student who must miss

-What is lost for the student who is absent?

-Does watching the recorded discussion compensate/have the same benefit as being present?

-Are there other mechanisms that could compensate as well?

-If so, what is the cost (in terms of time and effort) for the student and the instructor?

4. Questions about equity

-Do I have students who must miss my synchronous sessions regularly, perhaps because of a health issue or a location issue?

-If so, are there modifications I can make that ensure that these students are fully included in course activities, such as moving them to a different time, offering multiple (shorter) sessions, or making the discussion asynchronous?

If you do decide to record, keep in mind that any Zoom meeting recording that shows student names or faces is FERPA-protected course content, and should not be shared outside of the class where it was recorded. That means that sharing it in the password-protected online course for the students in that course or section is fine, but sharing the same recording on other sections or in future semesters would be inappropriate.

|

Reflect on the following questions: Looking back on your module structure that you developed in Part 1, how do synchronous meetings fit into that consistent structure? What will students do before the meeting to ensure that they arrive prepared for the meeting? How will you connect the synchronous and asynchronous parts of your course? |

|

On your own paper, make a list of what kinds of activities you typically do in a f2f meeting. Which of those are presentational and can be delivered asynchronously? Which are interactional and would work better as a video conference or synchronous online chat? |

This page is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.