Days of miracle and wonder

Normally, parents don’t rejoice at the sight of a wet diaper.

But this situation was different, because Jada Daves knew if her toddler son Shafer’s diaper was wet, that would mean his new kidney was working, which would mean his transplant was successful.

And it meant even more to Jada, because only hours earlier, the kidney that was now working in Shafer’s body had been in her own. Amazingly, her kidney had been a good match for her son.

“When you hope and pray and you want something so badly, you sort of hold your breath,” said Jada. “It was beyond words knowing the kidney was functioning—it was euphoria.”

It was quite a day, but Shafer has had quite a 21 months of life. Throughout his life, it seemed that as soon as one obstacle was cleared, another one developed. His has been a life characterized by urgency.

Shafer’s dad, Kevin Daves, an information technology senior developer, and mom Jada, a motivational speaker, live in Chattanooga and have four other children—Shayli, 9, Sharayah, 7, Shanel, 5, and Shah, 4.

The drama in Shafer’s life began early. He was born by emergency C-section on Oct. 15, 2009, with a prolapsed umbilical cord, when the cord (the baby’s lifeline) slips through the cervix during labor and into the birth canal before the baby does. This caused some tense moments, but after the birth things seemed fine. Jada brought Shafer home and the Daves family, now seven members strong, began to return to normal.

Normal didn’t last long. Shafer wasn’t eating, and when doctors examined him they discovered he had a rare condition, a congenital diaphragmatic hernia. He would need surgery to repair a hole in the diaphragm that allows organs to move into the chest cavity and restrict lung development.

And it was during treatment for one life-threatening condition that doctors discovered another.

The Daves were told that Shafer had Denys-Drash Syndrome, a genetic condition so rare that there are only 200 reported cases in medical literature. It is a chronic disease that leads to kidney failure by age 3 and the risk of development of a type of kidney cancer called Wilms Tumor.

The lesser of two evils: praying for kidneys to fail

The family turned to Vanderbilt for help.

Kathy Jabs, M.D., medical director for Pediatric Nephrology at the Monroe Carell Jr Children’s Hospital, is Shafer’s nephrologist.

“In my entire career I have treated five or six cases of Denys-Drash Syndrome,” said Jabs. “It is very uncommon and every patient is very different.”

Families dealing with this diagnosis face a wrenching choice about which treatment option to pursue: 1. To remove kidneys that are working when the child is small, or 2. Wait until the child has grown and dialysis and transplant are easier, but realizing that there is a risk that cancer will develop in the kidneys before they fail.

So, in one situation, patients actually “hope” to go into renal failure, which means removal of kidneys and dialysis, but which can lead to transplantation and takes away the possibility of cancer. The alternative: patients who develop Wilms Tumor, the cancer, have to undergo chemotherapy and must wait at least two years after completing the cancer treatments to be considered for transplantation.

“It’s not easy taking the wait-and-see approach,” said Jabs. “If we waited too long, he might develop the tumor. We did ultrasounds every three months.”

On Shafer’s first birthday, his kidneys failed—the situation his family had prayed for. He was transported to Vanderbilt on Oct. 15, 2010, where, as part of his treatment, both kidneys were removed and a daily, 11-hour dialysis routine began. Thoughts turned to a kidney transplant for Shafer.

Six of six? Really?

Kevin and Jada were tested as possible kidney donors for their son, but nobody was expecting much. Human Leukocyte Antigens (HLA) typing is a blood test that determines the major antigens or proteins that make each person different. Six antigens are important in kidney transplantations. Donors and recipients do not have to match all of the markers, but the closer the match, the better chance of a successful transplantation.

Parents usually aren’t great matches for their children.

But…

“When the coordinator called me, she said she had the most amazing news,” recalled Jada. “She said, ‘We don’t make this phone call often but you are a six of six match for Shafer.’

“For me to be a six antigen match— this was crazy miraculous.”

“Generally parents match on three of the six antigens,” Jabs said. “The six- antigen HLA match was lucky and made mom a better donor for Shafer.”

It was the first step in a lengthy testing process that can take up to six weeks. Just because somebody is a good match doesn’t mean they automatically become a donor.

According to Heidi Schaefer, M.D., Jada’s evaluating nephrologist, donors must undergo a score of tests to determine if they are medically suitable candidates for donation.

“We turn down almost half of all the donors presenting due to uncovered medical issues including high blood pressure, glucose intolerance or unsuitable anatomy,” Schaefer said. “[But] in this case, mom passed on all levels.”

And the question always comes up if an adult kidney will fit in a small child. The answer is yes—The transplanted kidney does not go in the same place that a normal kidney goes, but rather into the abdomen; and, although for a while he would have a bulge in his abdomen, everything would fit just fine.

A transplant date was set for June 6. The family was ramped up and ready to move to Nashville for the summer. Doctors advised the family to stay close to the hospital because the nearly six-week recovery process included frequent hospital visits for checkups. For the Daves, it was imperative that the entire family be together.

“This was our family’s journey,” said Jada. “As much as we needed to focus on Shafer, we have four other children, all under the age of 9, to be concerned about. We all needed to be in the same place.”

But just days before traveling to Nashville for transplantation, Shafer’s pre-surgery labs showed elevated liver enzyme levels. The transplant was delayed.

“I was just so ready,” said Jada. “When you hope and pray and want something so badly and you are on the cusp of it all happening and then the brakes are put on…I remember feeling like I had been punched in the stomach.

“That is where our faith comes in. God heard our cry and I believe he was honoring our prayers.”

Jada received a call on June 13 that refueled her hope—the transplant was rescheduled for June 22.

Goodbye dialysis, hello transplant

“Waiting for the transplant call is something you can’t describe,” said Jada. “Everything in your being is on ‘go.’ Everything is packed, loaded in the van and you are ready to hear the starting gun.

“For us, transplant was really the beginning of a long race. We have quite a road ahead of us—but we are ready to travel it.”

The night before the transplant the family gathered for a time of reflection, prayer and goodbyes.

“We sang a goodbye song to our dialysis machine,” Jada said, smiling at the memory. “We were saying goodbye to something that kept our child alive. But it was time to move forward.”

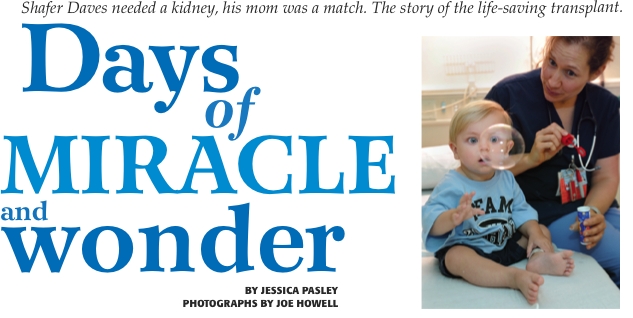

That team spirit continued the next morning. Sporting blue T-shirts emblazoned with “Team Shafer,” the family congregated on the third floor of the Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt.

Shafer and his parents were escorted to a holding room, while family and a host of friends assembled in a conference room to await news of the outcome. The family came together for last-minute hugs and kisses.

“I need you to be strong,” Jada told her children as they bunched up for a group hug. “It’s going to be OK,” Jada said. “I need you all to be strong and pray for mommy and baby Shafer, OK?”

And with that, Jada led her family in prayer, and after another flurry of hugs and kisses, she walked back down the hall to begin the next leg of the journey.

“The tears were unbelievable,” she said, overwhelmed by the sentiment. “I had never seen my children cry so hard. I was not prepared for that,” she said, pausing. “I was fine until I saw how upset they were.”

During a quiet moment just before the transplant, Kevin looked over at his wife and son on the gurney and exhaled.

“I feel like I am not really thinking,” he said. “I’m trying to be here in the moment.” Hoisting Shafer on his hip, Kevin leaned down to his wife. With his face nestled in her ear, he whispered loving words of comfort and motivation.

“There’s no easy way through this babe,” he said. “You’ve got this. God is going to walk you through this. I love you. I love you. We’ll see you in a

little bit.”

In O.R. 6, Jada was lifted onto the operating table and over the next few minutes each person was busy with their assigned tasks. The group worked in a synchronized fashion as they positioned Jada, the equipment and themselves around the table.

At 9:03 a.m. the surgeon made the first incision.

And then it was Shafer’s turn to leave for the O.R., as Kevin handed his son off to the transplant team.

Finish line

Doug Hale, M.D., assistant professor of Surgery, performed the donor portion of the operation. At 12:10 p.m. Hale gave the word to alert the surgical team with Shafer next door: the kidney was ready for transplant.

At 12:21 p.m. Jada’s kidney is extracted, placed in a sterile container and examined by David Shaffer, M.D., chief of the Division of Kidney and Pancreas Transplantation.

“It looks great,” said Shaffer, already on his way out the door, wasting no time. “Thank you,” he added over his shoulder.

Later, Shaffer explained why this surgery in particular was so special, and its context in the world of transplantation: “It’s wonderful that Mom was willing and able to donate,” he said. “Kidneys from living donors work better, last longer, have fewer complications, the recipient doesn’t have to wait on a long waiting list on dialysis and the transplant can be scheduled electively to optimize the recipient’s medical condition prior to surgery.

By 12:30 p.m. Kevin received word that the transplant team was at work, and was relieved to be called back to recovery. He spent the rest of the day at Jada’s bedside and saw Shafer later in the PICU.

After that memorable day (and the joy of seeing that wet diaper), Jada spent seven days at Children’s Hospital. She was discharged on June 28, and Shafer on June 30. Two weeks later the family settled into a routine in a rental home near the hospital.

“This was like running a marathon,” said Jada. “I feel like we have crossed the finish line. There are no words in the English language to talk about beauty of this transplant.

“After experiencing something like this, you are so grateful and thankful. The surgeons were phenomenal. They were the human vessels (hands) to give us this miracle. Life is good!”

Although Shafer was given a second chance at life, Jada recognizes that she too received a priceless gift—a new outlook.

With five children, a full-time job and a husband who balances work and home, the Daves’ lives are a carefully orchestrated hectic schedule.

“My perspective on life is different,” said Jada. “I am now taking more time to savor things. This experience has given me pause. You learn to embrace the possibilities and embrace what you have, right now, today.”

Shaffer, the transplant surgeon, said that happy outcomes are more dependent than ever on donors such as Jada. “There is an ever increasing disparity between patients waiting for organs and deceased donors,” he said. “Unfortunately, the number of deceased donors in the U.S. has leveled off and actually decreased in the last few years so at this point, increasing living donation appears to be the best way to transplant patients with the best possible kidneys.”

Both Kevin and Jada are looking forward to what the future holds. They both know that Shafer’s disease is life-long and he will continue to need medical treatment. But they feel that they can better manage the path ahead and have adopted a family motto: “Life isn’t about waiting for the storm to pass, it’s about learning to dance in the rain.”

“Transplant is a treatment, not a cure,” Jada said. “We know there will

be clouds so we have to learn to live in the now. That’s something we were missing before.”

Leave a Response