Huffman, Jennifer E., Gaziano, Liam., Al Sayed, Zeina Reda., Judy, Renae L., Raffield, Laura Marie., Biddinger, Kiran J., Charest, Brian R., Chopra, Anant., Gagnon, David R., Guo, Xiuqing., Koledova, Vera V., Levin, Michael G., Min, Yuan I. Nancy., Pirruccello, James P., Reza, Nosheen., Ruan, Richard., Verma, Shefali Setia., Verma, Anurag., Yao, Jie., Carr, John Jeffrey., Casas, Juan Pablo., Cho, Kelly M., Lima, João A.C., Post, Wendy S., Rader, Daniel J., Ritchie, Marylyn D., Shah, Amil M., Taylor, Kent D., Terry, James G., Rich, Stephen S., O′Donnell, Christopher J., Phillips, Lawrence S., Lunetta, Kathryn L., Rotter, Jerome I., Wilson, Peter W.F., Gaziano, John Michael M., Damrauer, Scott M., Kranzler, Henry R., Hung, Adrianna M., Assimes, Themistocles L., Whitbourne, Stacey B., Stephens, Brady M., Shayan, Shahpoor (Alex)., Ringer, Robert J., Pyarajan, Saiju., DuVall, Scott L., Churby, Lori L., Brophy, Mary Therese., Brewer, Jessica V.V., Oslin, David W., Matheny, Michael Edwin., Hauser, Elizabeth R., Tsao, Phillip Shih Chung., Deen, Jennifer E., Moser, Jennifer., Muralidhar, Sumitra., Sun, Yan V., Ellinor, Patrick T., Joseph, Jacob., Aragam, Krishna G. (2025). An African ancestry-specific nonsense variant in CD36 is associated with a higher risk of dilated cardiomyopathy. Nature Genetics, 57(11), 2682-2690. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-025-02372-2

Scientists have long known that dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM)—a condition where the heart becomes enlarged and weak—affects people of African descent at much higher rates, but the reasons for this have not been fully understood. In this study, researchers looked for a genetic explanation by analyzing DNA from 1,802 people with DCM and 93,804 people without the disease, all with African genetic ancestry (AFR).

They found a strong link between DCM and a specific genetic change in the CD36 gene, called rs3211938:G. This is a nonsense variant, meaning it turns the gene “off.” The variant is relatively common in people of African ancestry—found in about 17%—but is extremely rare in people of European ancestry (less than 0.1%). People who inherit two copies of this variant (about 1% of the AFR population) have roughly three times higher odds of developing DCM. Even among people who have no diagnosed heart disease, those with two copies of the variant show weaker heart function, with an 8% lower left ventricular ejection fraction, a key measure of how well the heart pumps blood.

In people of African ancestry, this single CD36 variant accounts for 8.1% of total DCM cases and explains about 20% of the excess risk of DCM compared with people of European ancestry.

Laboratory experiments using human heart cells grown from stem cells showed that losing CD36 function disrupts the heart cells’ ability to take up fatty acids—an important energy source. This leads to problems in cellular metabolism and reduces how effectively the cells can contract. Together, these findings suggest that loss of CD36 function and impaired heart energy use are major contributors to DCM in people of African descent.

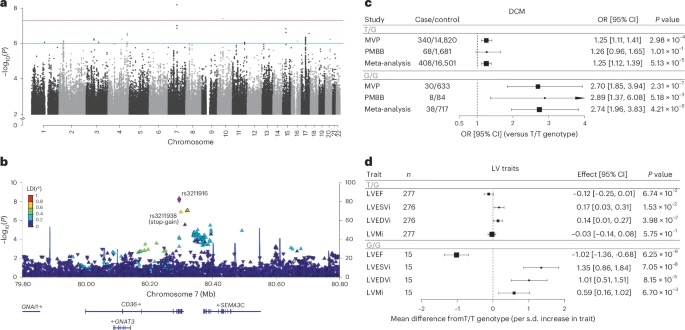

Fig. 1: Association of CD36 locus with DCM and validation of rs3211938 in left ventricular phenotypes among AFR individuals.

a, Manhattan plot showing the association between common genetic variants and DCM across the genome in AFR individuals. b, Regional association plot of the CD36 locus, displaying variant-level associations and linkage disequilibrium with the lead SNP (rs3211916) based on the 1000 Genomes AFR population. c, Association of heterozygous (T/G) and homozygous (G/G) rs3211938genotypes with DCM (versus the reference genotype (T/T)) in African ancestry participants of the VA MVP and PMBB, estimated using logistic regression adjusted for age, sex and the first ten principal components. Data are shown as ORs with 95% CIs. d, Associations of rs3211938genotypes with cardiac MRI-derived left ventricular traits in African ancestry participants from the UKB, MESA and JHS. Associations were estimated using linear regression adjusted for age, sex and the first ten principal components. Data are presented as the mean difference relative to T/T homozygotes (per s.d. increase in trait) with 95% CIs. Only the meta-analysis results are shown; full results are provided in Supplementary Fig. 6. LVESVi, left ventricular end-systolic volume indexed for body surface area; LVEDVi, left ventricular end-diastolic volume indexed for body surface area; LVMi, left ventricular mass indexed for body surface area.