Russo, Marissa N.; Norton, Emily S.; Ulloa-Navas, Maria José; Zarco, Natanael; Wang, Weiwei; Lam, Tukiet T.; Quiñones-Hinojosa, Alfredo E.; Belzil, Véronique V.; Guerrero-Cázares, Hugo. (2025). TurboID-Mediated Profiling of Glioblastoma-Derived Extracellular Vesicle Cargo Proteins. Journal of Extracellular Vesicles, 14(9), e70158. https://doi.org/10.1002/jev2.70158

Glioblastoma (GBM) is the most aggressive form of brain cancer in adults and is extremely difficult to treat because it almost always comes back after therapy. One reason for this recurrence is a small group of cells within the tumor called brain tumor–initiating cells (BTICs). These cells can resist treatment and interact closely with their surroundings in the brain, especially with other cells in a region called the subventricular zone (SVZ).

Communication between GBM cells and normal brain cells often happens through tiny particles called extracellular vesicles (EVs). These vesicles act like molecular messengers, carrying important biological materials—such as proteins and RNA—that can influence how other cells behave. In this study, researchers explored how EVs help GBM cells communicate with non-cancerous cells in the brain.

To do this, they used a special labeling technique called TurboID, which can quickly and efficiently tag all the proteins inside EVs. By activating TurboID in BTICs taken from GBM patients, the team was able to label and analyze the proteins inside the vesicles without damaging them. This analysis revealed that the EVs contain a wide variety of proteins, suggesting they play complex roles in tumor growth and resistance.

This study is the first to use TurboID to globally label EV proteins in primary GBM cells. The approach opens new possibilities for studying how GBM interacts with its environment, identifying potential biomarkers for diagnosis, and discovering new therapeutic targets to improve treatment outcomes for this devastating cancer.

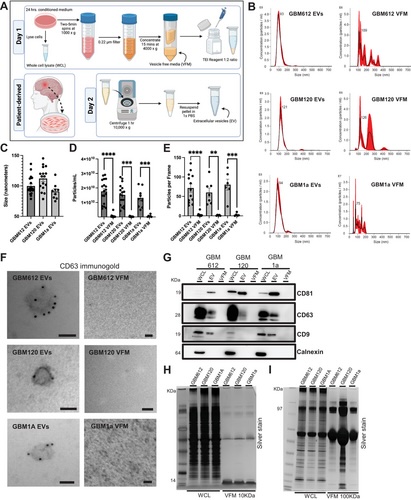

FIGURE 1

Successful extracellular vesicle isolation and characterisation using nanosight tracking analysis (NTA), immunogold electron microscopy, and western blot. (A) Schematic of extracellular vesicle (EV) isolation protocol from cell culture supernatant. (B) NTA histograms of vesicles plotting vesicles size to the concentration of vesicles per milliliter of sample. Size mode is indicated at the top of the peak. E8 stands for a scale of 1 × 108, E6 is 106, and E7 is 107. The red shading on each plot represents the standard deviation. All EV samples display one single peak whereas vesicle free media (VFM) samples all display multiple peaks of various sizes. (C) Summary plot of EVs size modes in nanometers between the three BTIC lines used in the study. All size modes fall into the category of smaller EVs and are <140 nm. n = 9–18. (D and E) Summary plot of particles/mL and particles/frame gathered from NTA for EV and VFM samples across the three BTIC lines. In all conditions, EV samples have significantly more particles/mL and particles/frame compared to VFM. n = 6–18. (F) Immunogold electron microscopy against CD63 shows gold particles labelling the surface of EVs, and no labelling or presence of EVs in the VFM fraction. Scale bars= 50 nm. (G) Western blot for brain tumour-initiating cell (BTIC) lines (612, 120, 1a) WCL, EV, and VFM probing for positive (CD81, CD63, CD9), negative (calnexin) EV markers. We observe positive markers in EV lanes, negative markers in WCL lanes only, no EV protein contamination in VFM. (H- I) Silver stain analysis for BTIC cell lines WCL and VFM comparing the VFM proteins when using 10 kD filter units and 100 kD filter units, respectively. Unpaired t-test, **p < 0.001, ***p < 0.0008, ****p < 0.0001.