Gao, Chenyu; Xu, Kaiwen; Kim, Michael E.; Zuo, Lianrui; Li, Zhiyuan; Archer, Derek B.; Hohman, Timothy J.; Moore, Ann Zenobia; Ferrucci, Luigi G.; Beason-Held, Lori L.; Resnick, Susan M.; Davatzikos, Christos A.; Prince, Jerry L.; Landman, Bennett Allan. (2025). Pitfalls of defacing whole-head MRI: re-identification risk with diffusion models and compromised research potential. Computers in Biology and Medicine, 197, 111112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2025.111112

To protect privacy, researchers often “deface” magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of the head before sharing them publicly. This process removes or alters the parts of the scan that show a person’s facial features. However, there is ongoing debate about how well this method actually protects privacy and how much it interferes with research that depends on detailed head or brain anatomy. With advances in deep generative models, it has become unclear whether defacing truly prevents faces from being reconstructed or identified from altered MRI data.

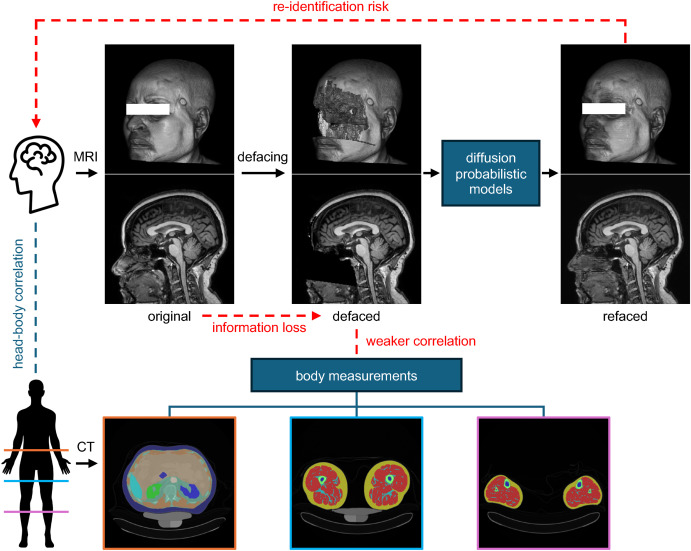

This study developed a “refacing” pipeline that can reconstruct faces from defaced MRI scans using cascaded diffusion probabilistic models (DPMs), a type of advanced deep learning model capable of generating realistic images. The models were trained on data from 180 subjects and tested on 484 previously unseen subjects, 469 of whom came from a different dataset. The study also examined whether the altered voxel data—the tiny 3D units that make up MRI images—still contain useful anatomical information. Specifically, it tested whether computed tomography (CT)-derived skeletal muscle radiodensity could be predicted from facial voxels in both defaced and original MRIs.

The results show that the DPMs could reconstruct faces that closely resembled the originals, with surface distances significantly smaller (p < 0.05) than those between the original faces and population-average faces. This indicates that defacing may not be sufficient to guarantee privacy, as realistic facial features can be recovered even after defacing. The refacing performance also generalized well to new datasets, meaning the technique worked consistently beyond the data it was trained on.

When it came to predicting muscle radiodensity, defacing was found to reduce accuracy. Using defaced images led to significantly lower Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients (p ≤ 10⁻⁴) compared to using original scans. For the shin muscle, predictions were statistically significant (p < 0.05) when using original images but not significant (p > 0.05) with any defacing method. These results suggest that defacing may not only fail to protect privacy but also remove valuable anatomical information that could aid medical research.

The study proposes two potential solutions to balance privacy and scientific value: first, sharing skull-stripped images (with the facial and cranial regions removed) along with measurements of those regions taken beforehand, though this limits research possibilities; and second, sharing unaltered images but enforcing privacy through strict data-use policies rather than through image alteration.

Fig. 1.

There are pitfalls of defacing, a technique used to alter facial voxels in whole-head MRIs to protect privacy. First, with deep generative models such as diffusion probabilistic models, it is possible to synthesize MRIs with realistic faces, which closely resemble the original faces, from defaced MRIs. This capability poses a re-identification risk, thus questioning the efficacy of defacing in protecting privacy. Second, facial and other non-brain voxels in whole-head MRIs contain valuable anatomical information. For instance, this information could be used to study correlations between head and body measurements using paired head MRI and body CT data. The alteration of these voxels results in information loss, thereby compromising such research potentials. The experiments in this paper are designed to showcase these two pitfalls.