Remedios, Lucas W.; Liu, Han; Remedios, Samuel W.; Zuo, Lianrui; Saunders, Adam M.; Bao, Shunxing; Huo, Yuankai; Powers, Alvin C.; Virostko, John; Landman, Bennett A. “Influence of early through late fusion on pancreas segmentation from imperfectly registered multimodal magnetic resonance imaging.” Journal of Medical Imaging 12 (2025): 24008. https://doi.org/10.1117/1.JMI.12.2.024008.

Combining different types of medical images—known as multimodal fusion—can help improve how well we can identify body parts in scans, like the pancreas. This is important for studying diseases like diabetes. However, scientists are still trying to figure out the best place in a deep learning model to combine these images. It’s unclear if there is one best method or if it depends on the specific type of model being used. Two big challenges in using multiple image types to study the pancreas are: (1) the pancreas and nearby organs can shift and stretch, making it hard to line up the images perfectly, and (2) people breathe during the scans, which also affects how well the images line up. Even with advanced computer methods to match the images, they’re often not perfectly aligned. This study looks at how the timing of fusion—whether early or late in the image analysis process—affects how well the pancreas can be identified using pairs of MRI scans.

We used 353 pairs of abdominal MRI scans (T1-weighted and T2-weighted) from 163 people. Each scan pair had a label showing where the pancreas is, mainly based on the T2-weighted images. Since the scans were taken during different breath holds, the images didn’t line up exactly. We used a leading method (called deeds) to align them as best as possible. Then, we trained several versions of a basic deep learning model (called a UNet) with fusion happening at different stages—from early to late in the model—to see which fusion timing worked best. We also tested another powerful model, nnUNet, to see if the best fusion timing changed.

Our results showed that using only the T2-weighted images, the basic UNet got a median accuracy score (called a Dice score) of 0.766, while the nnUNet got a higher score of 0.824. When we compared the fusion models to these baselines, we found that the best version of the basic UNet fused the images midway through processing, improving accuracy slightly by 0.012. For the nnUNet, the best version combined the images right at the start and had a smaller improvement of 0.004. These results were statistically significant, meaning the small gains were likely not due to chance.

In conclusion, combining different types of images at specific points in a model can slightly improve how well the pancreas is identified, but the best approach depends on the model. In datasets where the images aren’t perfectly aligned, fusion is a tricky process that still requires thoughtful design. More innovation is needed to handle these challenges in future research. The code for this project is available here: https://github.com/MASILab/influence_of_fusion_on_pancreas_segmentation.

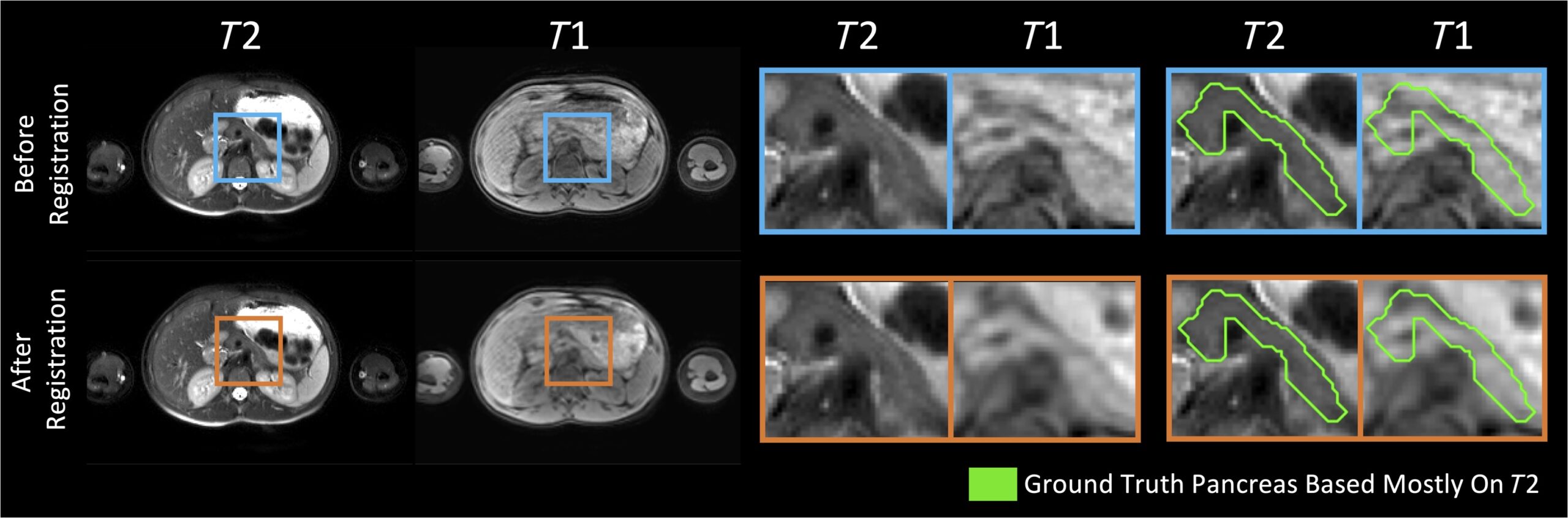

Fig. 1

Our pancreas labels were mainly drawn based on the T2w MR images. Despite the use of effective deformable registration, the pancreas labels did not always line up well with the corresponding anatomy in the paired T1w MR images from the same subject and same imaging session. For example, the T1w image shown exhibits poor alignment with both the T2w image and the pancreas mask, even after registration (bottom right). Persisting image misalignment makes it unclear how best to fuse T1w information to see gains in segmentation performance. The example shown exhibits particularly poor alignment.