Kang, Seung Woo; Helm, Bryan R.; Wang, Yu; Xiao, Shiyun; Zhang, Wen; Vasudev, Anusha; Lau, Ken S.; Liu, Qi; Richie, Ellen R.; Hale, Laura P.; Manley, Nancy R. “Insulin-Like Growth Factor 2 as a Driving Force for Exponential Expansion and Differentiation of the Neonatal Thymus.” Development (Cambridge) 152, no. 7 (2025): dev204347. https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.204347.

Like other organs, the thymus—which plays an important role in the immune system—grows quickly during early development but stops growing after birth. Scientists have long wondered what causes this shift, but the exact reasons have remained unclear.

In this study, researchers used a technique called single-cell RNA sequencing to closely examine the thymus in mice at different stages of development. They found major changes happening in two types of support cells in the thymus: endothelial and mesenchymal cells. These changes were especially noticeable during the time when the thymus stops growing and enters a stable phase, called homeostasis.

One key finding was that a protein called insulin-like growth factor 2 (IGF2), which is produced by fibroblasts, appears to play a major role in helping the thymus grow right after birth. IGF2 specifically encourages the growth of cortical thymic epithelial cells, which are important for the thymus to function properly. This growth is carefully controlled and slows down once the thymus reaches its mature size.

To see if this also happens in humans, the researchers looked at RNA data from human thymus samples and found similar patterns, suggesting this growth mechanism is shared across species.

Overall, the study shows that fibroblast-derived IGF2 is a key factor that helps the thymus grow in early life and then quiets down to allow the organ to stabilize. This insight helps us better understand how the immune system develops.

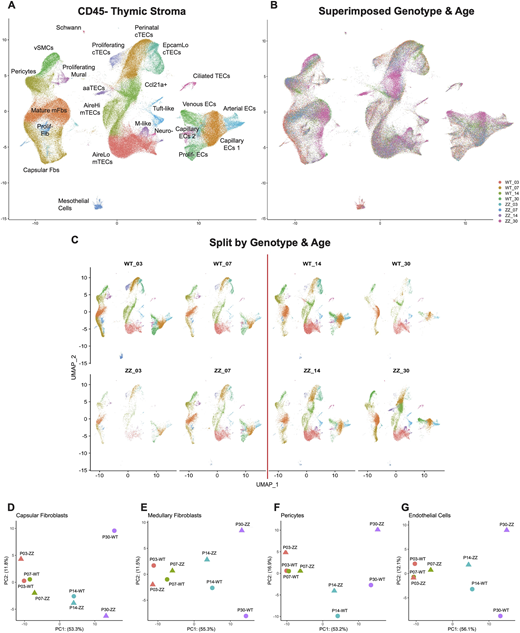

Fig. 1

scRNAseq of total thymic stroma from Foxn1lacZ shows dynamic stromal changes after the perinatal transition point. (A) UMAP visualization of 206,271 CD45− total thymic stromal cells with annotations. (B) UMAP visualization of superimposed datasets split by age and genotype. Foxn1lacZ wild-type littermates and Foxn1lacZ/lacZ homozygotes are denoted by WT and ZZ, respectively. Numbers indicate the age of the datasets. (C) UMAP visualizations of merged dataset split by age and genotype. The red line indicates postnatal day 10, a thymic transition point from neonatal expansion to juvenile homeostasis (the perinatal transition point). (D-G) PCA plots of pseudo-bulked data classes split by age and genotype.