SUMMARY

UNIFYING THEME: Information Marketplace: Ensuring the Public has the Data

Despite conventional wisdom, behavioral evidence repeatedly suggests that most Americans are not avid consumers of political news. Instead, they are spending an astounding amount of time engaging with entertainment media. It is time to face the extent to which politics and non-political media consumption are closely intertwined. The role of 'The Apprentice' in the rise of President Trump is one such example. Going forward, politicians need to rewrite the standard political playbook to reach an inattentive public.

by Eunji Kim, Assistant Professor of Political Science

In 2014, Jimmy Kimmel Live! show asked random people strolling on Hollywood Boulevard to identify Joe Biden. Six years into the Obama-Biden administration, their answers ranged from a terrorist to "that old dude" from Pineapple Express, a comedy movie about a drug dealer. Unfortunately, this mockery of the uninformed public reflected reality. According to a national Pew Research Center survey in 2010, four out of ten Americans didn't know Joe Biden was vice president.

One of the most under-appreciated truths about American politics is that most citizens are neither interested in politics nor avid consumers of political news. While we talk about the growing polarization between Democrats and Republicans, the deeper divide is between those who follow politics and those who are not interested in it. We worry about hyper-partisan news and fake news (and rightly so), but Fox News-"the most watched cable news channel" -attracts only 3 million viewers during an average primetime. In contrast, Tiger King attracted 34 million viewers within the first 10 days of its release.

This pattern has not always been true. As recently as when Bill Clinton was president, watching an evening news program during dinner was still a daily ritual for most American families. Once upon a time, America's most-watched TV program was CBS's 60 Minutes. But in vying for Americans' attention, President-elect Joe Biden now faces fierce competition from lip-syncing teenagers on TikTok, viral prank videos on YouTube, and live webcams of the Smithsonian's Giant Panda.

Are you unconvinced? After all, don't people consume the news in different ways now? Maybe the audience for traditional TV news programs has been shrinking, but don't people consume news via smartphones, computers, and tablet PCs from Facebook or Twitter? What about headlines like "70% of People Say They Get News from Facebook" and "More Americans Are Getting Their News from Social Media"?

The problem is that the overwhelming majority of these news consumption statistics are drawn from surveys. That is, these are self-reported answers to questions like: "How often do you get your news from social media?" Pew's survey, for instance, reported that 55% of U.S. adults picked "often" as an answer. But people don't necessarily tell the truth in a survey. They want to say that they voted even when they haven't, that they are extremely interested in politics when they are not, and that they care about political issues when they haven't really thought them through. Social scientists are well aware of the limitation of these inflated survey responses, but surveys are often the only tools available to measure and assess political behavior.

Recent methodological innovations have brought behavioral data to the study of how Americans consume the news. One of the most exciting developments has been the use of web-tracking data. We no longer have to ask how often you consume news or visit Facebook. Web-browsing records tell us the precise amount of time spent on each URL. Political communication scholars have been ecstatic to study questions ranging from partisan selective exposure to fake news consumption.

These studies have shown that most people are not consuming very much news online either. In order to study topics like "partisan echo chamber," for instance, social scientists needed a sample of web-browsing activities in partisan news sites, ranging from Breitbart to Huffington Post. They had access to the web-browsing activities of a whopping 1.2 million people, but only 50,000 of them had read a bare minimum dose of news online: "at least 10 substantive news articles and at least two opinion pieces" over a 3-month period. In other words, during a quarter of the year 2013, only 4% of internet users read 12 news articles on average, or approximately one news article per week. That does not suggest Americans are frequent consumers of the news through social media, despite their claims via public opinion polls.

Other statistics tell similar stories about how Americans are avoiding the news. In 2015, one study that examined 6,319,441 web-links visited by 1,392 respondents find that only 83,006 visits can be coded as related to political news. In other words, only 1.3% of web-traffic went to news. A year later, even during an election year as highly contentious as 2016, the number didn't change much. It was up to 1.9%.

Though another study finds the share to be 4%. That is better, but hardly grounds for optimism. Further, it is worth noting that these web-browsing data are coming from respondents who willingly consent to have their internet behavior to be measured by researchers. Not surprisingly, they are more interested in politics than a nationally representative sample. In other words, these numbers are actually over-estimates.

What are the consequences of most citizens opting out of consuming news? Much ink has been spilt on how the changing composition of the attentive electorate contributes to more polarization. Yet when it comes to the electoral processes, it means that those who can attract people's attention have the upper hand. Name recognition and personal brand are invaluable assets now. And you may have heard of one example: the rise of Donald Trump.

While diverse scholarly literature has emerged to explain his improbable 2016 victory, conventional wisdom places Trump's The Apprentice center stage. As one journalist bluntly argued: "You might think that the rise of president-elect Trump is down to sexism, or social media filter bubbles, or a country's ability to put partisan politics ahead of personal judgment, or the dying roar of a frightened white majority. But it isn't. It's because of The Apprentice."

The Trump presidency, of course, is an embodiment of America's long-standing sins and political realignment. Yet the counterfactual is difficult to imagine. Without the persona and reputation Trump developed a decade before seeking office through a popular reality TV show, would he have been able to secure the Republican nomination and ultimately the presidency?

Open-ended answers in an original national survey conducted right before the 2016 election serve as a window into voters' decision-making. For Trump supporters who never watched The Apprentice, the reasons for their electoral support were mostly focused on political issues such as trade, foreign policy, or immigration. Among those who were avid fans of The Apprentice, their reasons were all about his character or business expertise: "He is real." "He says the things everyone is thinking, but no one has the guts to say out loud." "Businessman and not a politician."

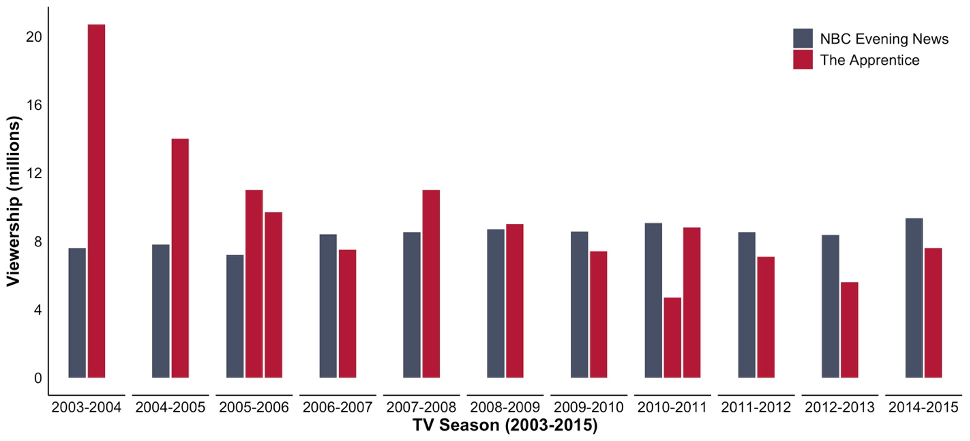

These reasons align with the phrases that contestants used to describe Trump throughout The Apprentice. Trump was portrayed as one who "has certainly given everybody a shortcut to the American Dream" (Season 1:Episode 1); "one of the most powerful men in the world" (S2:E1); "A humanitarian. And somebody who's also concerned about important causes" (S4:E13); Or "An icon. …an amazing individual and everybody looks up to [Trump] (S7:E13). The Apprentice attracted three times the audience as NBC Evening News in its first year, and continued to attract a larger or similar audience than the evening news until 2015. As of October 2020, almost 70% of Twitter users who follow @NBCApprentice also follow Donald Trump.

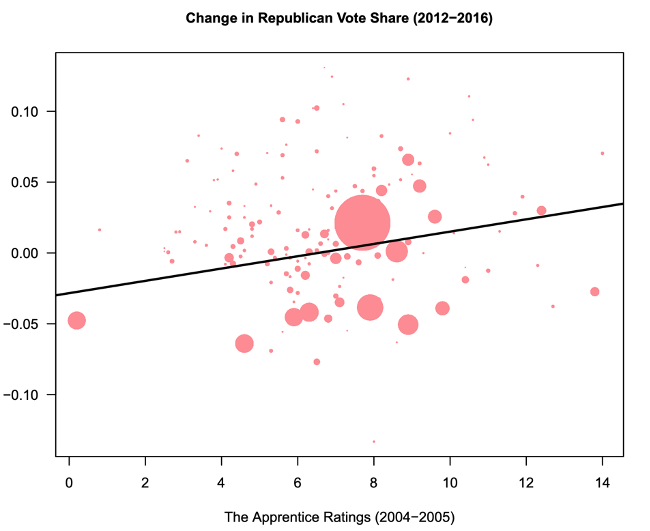

Nielsen data confirms this pattern as well. At the media-market level, The Apprentice ratings in 2004-the year at its peak popularity-are positively correlated with % change in Republican vote share from 2012 to 2016. In other words, geographic variation in the popularity of The Apprentice almost a decade ago can predict the areas that gave more support to Trump than Romney, even after taking into account for standard demographic factors. Such data may not be a smoking gun, but they are highly suggestive.

The bottom line is that politics and non-political media consumption are more closely intertwined than any of us imagined. Social science is now accumulating rigorous causal evidence on the power of entertainment media in the electoral process. For instance, exposure to Ronald Reagan as an entertainment television host in the 1950s made his presidential bid successful. In Italy, citizens who watched more entertainment TV as children ended up voting for the populist party decades later. Voters in Ukraine elected as president the comedian Volodymyr Zelensky, who is best-known for starring in one of the country's most popular television series in which his character accidentally becomes Ukrainian president.

In this age of political inattention, governing is inherently thorny and communicating is impossibly difficult. President Obama frequented late-night comedy shows, yet for a while they have been the spearhead of satire only for blue America. Reaching out to the inattentive public may require unusual approaches to presidential messaging, even if it means setting up a virtual Biden Island in Animal Crossing, a squishy Nintendo game.

Further Reading:

- The effect of big-city news on rural America during the COVID-19 epidemic, August 2020. Proceedings of the National Academies of Science

- Identifying the Effect of Political Rumor Diffusion Using Variations in Survey Timing 2019. Quarterly Journal of Political Science 14(3): 293-311.

- Does Newspaper Coverage Influence or Reflect Public Perceptions of the Economy?" (with Daniel J. Hopkins and Soo Jong Kim) 2017. Research & Politics 4(4): 1-7.

- Media Effects on Retrospective Economic Perceptions: Partisan Media and Its Implications for Economic Voting. 2017. The SAGE Handbook of Electoral Behavior 733-758.

- https://www.pewforum.org/2010/09/28/u-s-religious-knowledge-survey-who-knows-what-about-religion/

- Yanna Krupnikov and John Barry Ryan. Forthcoming. The Other Divide: Polarization and Disengagement in American Politics. Cambridge University Press.

- We have seen how conspiracy theories on social media can mobilize a small subset of highly engaged people to storm the Capitol for the first time since the War of 1812.

- Flaxman, Seth, Sharad Goel and Justin M Rao. 2016. "Filter bubbles, echo chambers, and online news consumption." Public Opinion Quarterly 80(S1):298-320.

- Andrew Guess. Forthcoming. "(Almost) Everything in Moderation: New Evidence on Americans' Online Media Diets." American Journal of Political Science.

- Andrew Guess (forthcoming) finds that out of 16,984,969 total visits (N= 2,512 respondents) from October 7-31, 2016, only 328,073 visits are coded as political news.

- See Markus Prior. 2007. Post-Broadcast Democracy. Cambridge University Press.

- Other examples abound. Sean Duffy, once a cast member in The Real World: Boston, a MTV reality television show, is now the U.S. Representative for Wisconsin's 7th congressional district. From Cynthia Nixon and Stacey Dash to Surya Yalamanchili and J. G. Hertzler, there is approximately a hundred known cases of celebrities who have sought various electoral positions in the last twenty years.

- Shawn Patterson, Heyu Xing and I collected an original national survey via Survata platform in October 2016 with N=932 white voters.

- There was even a scene in which Senator Chuck Schumer (D-NY) lent credence to Trump's success, saying that "even when [Trump] was much younger," he knew that "[Trump] was gonna go places" (S5:E8). One episode in Season 6, aired in 2007, featured a person holding a "Trump for PRESIDENT" sign in one rally at Minnesota.

- Shawn Patterson, Heyu Xiong and I scraped twitter handles of every user who follows the @NBCApprentice account (N=114,121 as of October 2020), and cross-checked whether each user also followed a top Republican primary candidate in 2016. Fewer than 15% of The Apprentice fans follow other Republican politicians, while 69% of them follow Donald Trump on Twitter.

- The size of the circles is proportional to media market-level (DMA) population. The bivariate relationship is positive and statistically significant at p <0.05 level.

- Heyu Xiong. Forthcoming. "The Political Premium of Television." American Economic Journal: Applied Economics; Durante, Ruben, Paolo Pinotti, and Andrea Tesei. 2019. "The Political Legacy of Entertainment TV." American Economic Review 109 (7): 2497-2530.

- New York Times