Reflections on GIS Day 2016

On GIS day (and please, do visit us at the Center for Digital Humanities Open House this November 16th, from 1:00-3:00 pm), I wanted to take a closer look to the role of GIS in the current stage of development of the Digital Humanities. I am looking forward to celebrating GIS day as any other self-respecting geek would: with David Bodenhamer’s talk “Developing the Spatial Humanities: More than GIS”, hosted by the Center for Digital Humanities at 4:10 pm. This issue is near and dear to my heart: as an archaeologist, GIS is a critical and increasingly important tool in my field of research. When I look at the Digital Humanities, I hope we also to integrate the role of materiality and spatiality in this digital era in which objects and boundaries are blurry. What is the role we, as one of the most intrinsically material-rooted of social scientists (and I make this claim from the memories of years of fieldwork spent marvelling at walls, categorizing diminutive ceramic sherds, and sifting soils hopeful to find a single corn cob we could date), have in the Digital Humanities?

One of the ways in which archaeology was drawn into the Digital Humanities was through the Spatial Humanities. As Harris, Corrigan and Bodenhamer (2010) point out, we owe a great debt to geography as a “bridge” between the humanities and social sciences. This interest in space has moved on (intentional pun!) to include an interest on time and “deep mapping”, defined by Bodenhamer, Corrigan and Harris (2015: 3-4) as “a platform, a process, and a product. It is an environment embedded with tools to bring data into an explicit and direct relationship with space and time; it is a way to engage evidence with its spatiotemporal context and to trace paths of discovery that lead to a spatial narrative and ultimately a spatial argument; and it is the way we make visual the results of our spatially contingent inquiry and argument.”

One of the ways in which archaeology was drawn into the Digital Humanities was through the Spatial Humanities. As Harris, Corrigan and Bodenhamer (2010) point out, we owe a great debt to geography as a “bridge” between the humanities and social sciences. This interest in space has moved on (intentional pun!) to include an interest on time and “deep mapping”, defined by Bodenhamer, Corrigan and Harris (2015: 3-4) as “a platform, a process, and a product. It is an environment embedded with tools to bring data into an explicit and direct relationship with space and time; it is a way to engage evidence with its spatiotemporal context and to trace paths of discovery that lead to a spatial narrative and ultimately a spatial argument; and it is the way we make visual the results of our spatially contingent inquiry and argument.”

So, here comes archaeology.

As David Bodenhamer implies in his talk title, GIS is not the only or even most adept way to conduct deep mapping in these days. Virtual Reality, for one, provides new ways to experience archaeological sites, and hopefully one day excavations themselves. However, what else can we get from GIS within the Digital Humanities? GIS can ideally provide a layout for “deep mapping” historical processes in a way that can be then accessible to different users as a mean to continuously develop new research questions, new ideas, and new science.

In the last 5 years, GIS has increasingly gained terrain as the most versatile and comprehensive use for spatial analysis in archaeology. It has also become a core instrument for data collecting, as different mobile GIS apps have made their way right into our excavations units. Now for the first time, archaeologists can have results just from the data gathering process, and can get answer to questions within days of finishing their excavations: is there a pattern in material distribution? Is there any location within the sites that was a preferred route of passage or even a controlled area? Where the natural features surrounded the site influential in site selection?

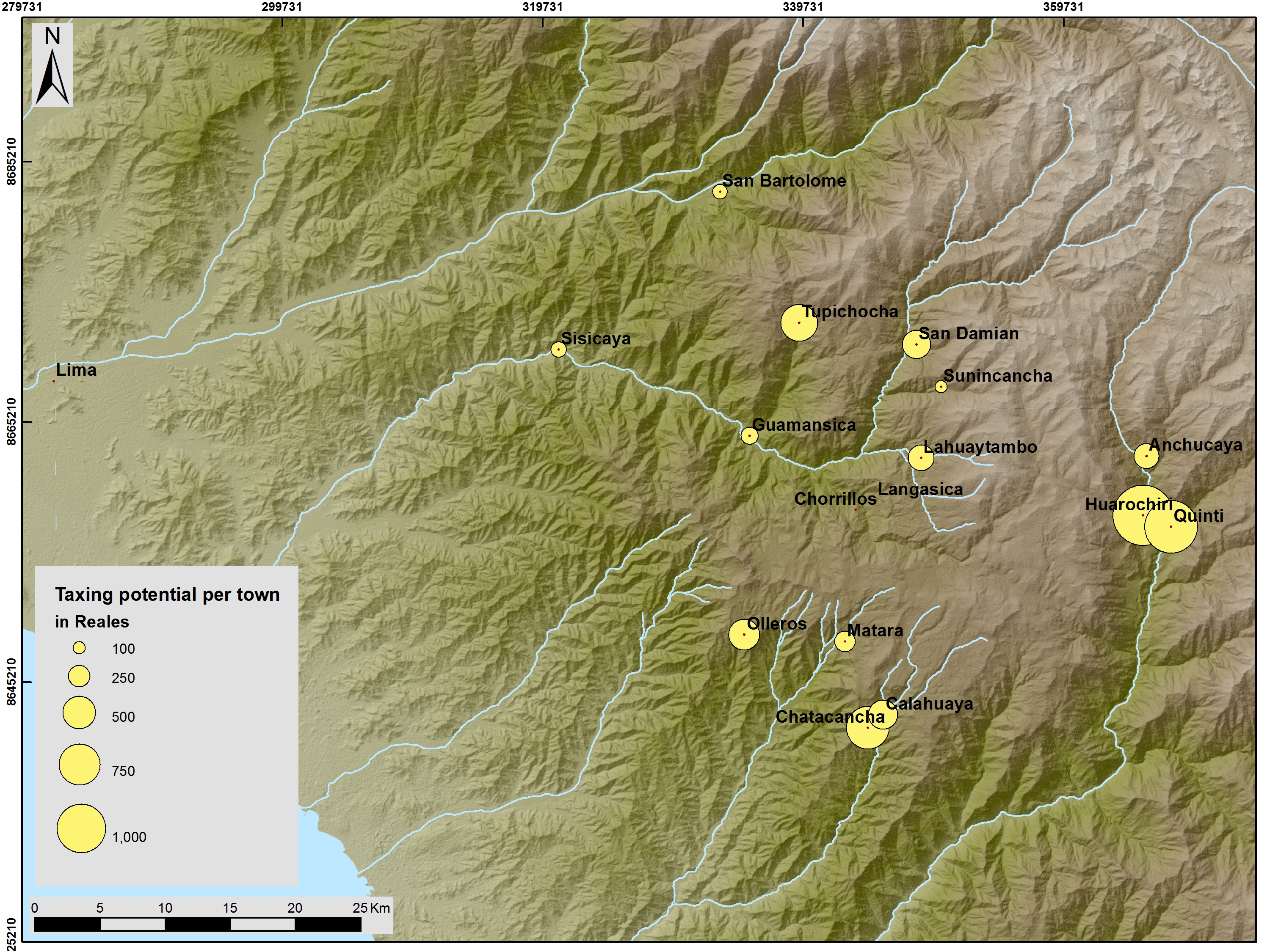

Then again, the Digital Humanities is not just archaeology with computers, and we need to think of a way in which our digital information can reach a wide array of people and be easily understandable. Last week Vanderbilt was one of the sponsors of the American Society for Ethnohistory 2016 Annual Meeting (http://www.ethnohistory2016.com/). Besides the overall quality of my colleagues’ papers, I was impressed to see some really ingenious applications to GIS just to map this deep time: from movement within sites, to understanding the relationships between settlements and fields, GIS served to recreate different dimensions of the human experience of movement, time and place. My co-author and I presented a paper that was mostly historical: we worked with an 18th century Spanish document from Peru and tried to map the movements of Spanish colonial officials from to town to town as described by them. We wanted to see if travel itinerary was at all doable or a blatant lie. Besides the fun that it is arguing the veracity of a document through mapping, the potential application of this type of historical research was very vivid in our minds. Most archaeologists just won’t read colonial documentation unless it’s already paleographed. And once it is, there is still the matter of going through pages and pages of “official” text before you get to the nitty gritty of it. If all this documents could be made available through interactive mapping, how much easier would it be to study past societies? How much more reachable history and archaeology would be to a wider audience? And how much more timely would we be able to just give our research results to the communities we work with, without the need for the venerated researcher explaining it?

As an archaeologist, I feel that GIS has provided me with the tools to democratize my research, as much as democratization is limited by accessibility to hardware and software. I can now put both my raw data and spatial analysis results out there in a way that is replicable and engaging. At the end of my dissertation, I envision finally having the time to really put this proposal in place and see how people that are not specialist on a single area, time period, or social science, can play with my data and come with understandings that evade me. I particularly long to just bringing this database of colonial documents and archaeological datasets nicely presented in interactive maps to the children of the communities I work with in the Peruvian Andes, and see them engage with archaeology as active agents and creators, and not just by hearing me drone on and on about my excavations. Here we can finally have the tools to enable multivocality and co-production.

And yes, there are many tools now that can surpass the flexibility of GIS, but not that many that are quite as powerful a research tool and lend themselves to interactive presentations.

Here’s to another year of GIS, and to always finding new ways to express our research!

-Carla Hernández Garavito