Digital Humanities, Analog Style

by Laura Carpenter, Mellon Faculty Fellow for the Digital Humanities, Department of Sociology

When I applied to spend a year as a Mellon Faculty Fellow at the Center for Digital Humanities, knitting was the last thing on my mind. Sure, I knew how to knit—my mother was a home economics teacher, after all—but it had been years since I’d picked up needles and yarn. My plan for the fellowship year centered on constructing a companion website for Throw Momma on the Train, the book I’m writing about gender, generations, and family journeys.

In an ordinary academic year, constructing that website might have remained the sum total of my digital humanities endeavors. But, of course, the Covid-19 pandemic has made this no ordinary year. As spring 2020 wore on, and a few weeks of sheltering in place transmogrified into staying home until further notice, I found myself yearning to construct things by hand.

Now, I’ve always nurtured a creative impulse alongside my scholarly pursuits as a sociologist. My work with photography has long informed my teaching and research, especially my course “Seeing Social Life.” I also enjoy textile arts and crafts. Needlepoint, cross-stitch, embroidery, knitting, and sewing—I’ve tried them all. My recent adventures in textile creation have mainly involved sewing. I’ve led workshops on repurposing discarded clothing and even made an “ugly Christmas” party dress out of recycled t-shirts. But as the coronavirus crisis deepened, I felt increasingly drawn to fiber arts that involve a more repetitive technique. Needlepoint, with its recurring rows of slanting stitches, for example, or knitting, where a small vocabulary of needle-hand-yarn movements are repeated to bring a cloth item into form. In pandemic times, knitting was just what I needed.

The more digital my work and social life became, the more I took cultivated, and refuge in, the analog arts. There is something remarkably powerful about making things with your hands. The transformation of materials can astonish and delight. Knitting and crochet both involve looping a long strand of yarn—essentially, a string—into an appealing, useable object, be it sweater, afghan, or soft toy. Making things can also be soothing, keeping one’s body busy so as to give one’s mind space to wander.

As it turns out, I wasn’t the only scholarly soul wandering the virtual knitting supply aisle. One of the workshops in this summer’s online Digital Humanities Bootcamp (attended by all the 2020-21 DH fellows) explored a number of virtual exhibits, including one called “Knitting Data: Data Visualization and Crafts.” Curated by Rebecca Michelson and colleagues at the University of Southern California, the exhibit showcases projects that use knitting and crochet to display different kinds of data, from blankets depicting sleep cycles to sweaters charting shifts in the wild tiger population.

As a social scientist with a textile craft habit, I was utterly captivated by these projects. Data and knitting, together—heaven at last! I was particularly struck by the Tempestry project, in which volunteers knit or crochet tapestries representing one year of daily climate data from a particular locale. Placed side by side, these creations vividly demonstrate how weather is growing increasingly unruly around the globe. Importantly, in the act of hand-creating these objects, project participants gain an embodied sense of changing climate conditions in relation to the social world.

Suffice to say, I felt the urge to visualize humanistic social science data using a similar technique. Given my research interests in health and medicine, it wasn’t long before I decided to develop a system for presenting US state-level daily covid-19 mortality data as color-coded knitted wall hangings. I began by selecting three states of similar population size which vary in terms of epidemiological conditions and public policy responses to the pandemic: Tennessee, Massachusetts, and Maryland.

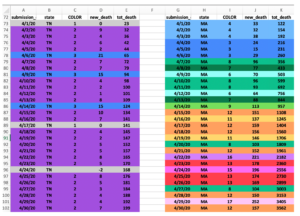

Each hanging charts the period from February 1, 2020, to January 31, 2021, with one row of knitting symbolizing one calendar day. To symbolize the virus name, each piece is 19 stitches wide. The type of yarn I chose determined the size of knitting needles to be used, and thus the size of the piece. Each completed hanging will be approximately 4 inches wide and 4 feet in length. The color code chart is depicted in Figure 1; each of the 17 hues represents an interval of 15 deaths from covid-19. After color-coding spreadsheets for each state (see Figure 3), I picked up my knitting needles and yarn skeins and got to work (see Figures 4 and 5). Figure 2 shows the in-progress first “draft” of the piece representing Tennessee.

Figure 1: Color Key

Figure 2: Tennessee Visualization in Progress (white threads mark the beginning of each month)

Figure 3: Color-coded CDC daily covid-19 mortality data for April 2020 from Tennessee (left) and Massachusetts (right)

Figure 4: In-progress knitted display for Tennessee; detail showing covid-19 mortality for April 2020 (month runs top to bottom)

Figure 5: In-progress knitted display for Massachusetts; detail showing covid-19 mortality for April 2020 (month runs top to bottom)

Made by hand from everyday, humble materials, these textile pieces visualize data in tangible, familiar, comprehensible form—a form of public sociology, if you will. The hangings are tactile, aesthetically appealing, and even useful (they are, fundamentally, scarves). Displaying the subject matter of medical sociology, these textile pieces evoke central issues in sociology of knowledge (how do choices about color and category size shape what we know?), embodiment (what does physically fashioning such items accomplish?), and death and dying (through what rituals do we mourn?). Moreover, because textile crafts such as knitting are associated with women, and consequently often dismissed as trivial, the project additionally evokes key concerns in the sociology of gender and feminist science and technology studies, not least how the social identities of the people who create data displays, and the gender and racial/ethnic connotations of the technologies they use, affect interpretations of those displays.

My covid-19 knitting project embodies the digital humanities in multiple ways. Electronic media have been critical in facilitating the project. Covid-19 morbidity and mortality data have been made available digitally to the general public in nearly real time. (I used datasets from the Centers for Disease Control.) When complete, I expect to share the project online as part of a digital exhibit on the social threads connecting people who knit and crochet and who share those skills with others. (I am co-creating this exhibit with Cynthia Gadsden, Assistant Professor of Art History at Tennessee State University, whom I met through the Mellon Partners in Humanities Education consortium.)

There is another, more literal, sense in which my project embodies digital humanities. I am using my digits—fingers and thumbs—to manipulate yarn and needles to fashion objects that speak about human existence, and which also can be put to human use. The creative, embodied craft that is keeping me grounded in difficult times also expresses the terrible burden being borne, with differential intensity, by different social groups. At times, I have felt troubled to be making attractive objects to address a worldwide human tragedy. Yet, commemorating human loss through beautiful creations is a time-honored social tradition.

It is, of course, no coincidence that social life is often discussed using the metaphor of fabric woven, torn, or mended.