GPT No Habla Español-Part 2- Cide GPTmete Benengeli: In search of a missing manuscript

By Caroline B. Colquhoun and Sahai Couso Díaz, Mellon Graduate Student Fellows for the Digital Humanities 2020-2021, CMAP, Department of Spanish & Portuguese

At least three motivations propelled us to tackle the task of fine-tuning OpenAI’s GPT-2: our previous foray into fine-tuning, the inherent linguistic biases in tech (discussed in our last post), and Ole Molvig’s inspirational Talk to Einstein project. Of course, as is often the story with digital humanities projects, nothing was as straightforward as we might have hoped.

As Molvig suggests, synthetic text has the potential of working as a “discovery engine” for archival inquiry. This is to say, by fine-tuning an AI model like GPT-2 on the texts of a particular author, scholars who “converse” with these AI transformers engage in a sort of meta-archival interrogation of the “mind” and works of a now-inaccessible thinker. Such “conversations” could enable us to unearth novel connections and new insights about the archives in question. Reflecting upon our own observations after successfully fine-tuning a GPT-2 model to (co-)write a screenplay “in the voice of” James Cain,[1] we began to ponder the potential applications of the same tools and processes to our home discipline and our native (Sahai) and chosen (Caroline) language of Spanish. If fine-tuned using a corpus of texts by canonical Spanish-speaking authors, could GPT-2 identify unexplored patterns of meaning in the archive of Hispanophone classics? Could GPT-2 help us confirm or reinforce a hypothesis about the authors’ complete oeuvre or an individual text? Could conversations with AI versions of classic writers of Spanish letters create new masterpieces?

As a proof of concept and our first experimental Spanish synthetic text generator, we decided to “create” Cide GPTmete Benengeli, an AI model fine-tuned with a corpus of Golden Age Spanish author Miguel de Cervantes texts, named as an homage to Cide Hamete Benengeli, the intratextual “author” of the chivalric novel Don Quixote. In Cervantes’s well-known and abundantly-translated masterpiece, the author plays a number of metafictional games with the reader, and Cide Hamete is among them. Following a prologue in which Cervantes denies his own authorial role in the work, the novel’s narrator reveals–eight chapters in–that he is merely retelling a story from a parchment he stumbled upon by chance. As it happens, the original “author” of the story of Don Quijote and his squire, Sancho Panza, is one “Cide Hamete Benengeli,” an Arab Muslim. What is more, the work has subsequently been “translated” from the “original” Arabic into Spanish, and the voice of the intratextual translator chimes in with his own comments and critiques as the work progresses. Within the novel, the tangled narratorial web serves as a social commentary, a metaliterary feature, and/or a part of Cervantes’s complex and comprehensive generic parody; for our purposes, it felt fitting to borrow the name of the famed fictional author of this layered and polyphonic tale.[2]

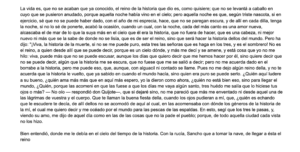

In our first fine-tuning attempt, we followed the same process we’d previously employed (using the very user-friendly Google Colab notebook created by Max Woolf), and this time used a corpus of Cervantes texts (his Novelas ejemplares and the two volumes of El ingenioso hidalgo don Quijote de la Mancha). The results, however, were not ideal. GPTmete was producing texts in something like Spanish–the vocabulary was recognizably Spanish, the text generator was inserting recognizable character names, and the results replicated the dialogue-heavy style of both the Novelas and the Quixote. Syntactically, the grammatical elements were in mostly the right places. The problem, however, was that it didn’t make any sense.

GPT-2 was not succeeding in producing actual, comprehensible Spanish the way it is able to do in English. Our first attempt was not a total failure, but it prompted us to reflect a little more on the nature of GPT-2 itself. As we mentioned in our previous installment, GPT-2’s original training corpus is primarily in English, so while it mastered the grammatical nuances of the internet’s lingua franca, its Spanish left a lot to be desired.

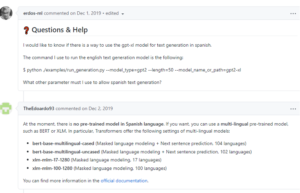

As it happens, the issue we observed was a known one. See this github exchange about how to use GPT-2 text generator in Spanish:

Nevertheless, we were adamant about finding a solution–and about using GPT-2. Recognizing that we needed to take a step (or five) back, and that perhaps we were the ones who needed to train and fine-tune ourselves a bit more, we began to seek out other projects that used GPT-2 in non-English applications. Our initial searches yielded a couple of successful findings, and even more non-English GPT-2 projects been published since we first began investigating the issue in summer 2020:

- A researcher at the University of Brasilia developed GPorTuguese-2. His strategy was fine-tuning on a pre-trained model instead of training from scratch. His language model for Portuguese text generation wraps Hugging Face’s Transformers and Tokenizers libraries in fastai v2.

- Then, there was this project to fine-tune a German GPT-2, again from the Hugging Face model hub. The creator combines the transformer’s library with a text dataset of German recipes–GPT turned chef de cuisine, or Küchenchef, as it were.This tutorial also pointed us to a couple of recently published Hugging Face Spanish datasets that may prove useful to the development of our own project: Spanish_Billion_Words and Large_Spanish_Corpus.

- These are several examples of projects in Chinese: “Generating Major Types of Chinese Classical Poetry in a Uniformed Framework”, and “A Human- Machine Collaborative Chinese Classical Poetry Generation System”.

- A group of Italian researchers created GBGePpeTto, the first generative language model for Italian. The model was built with GPT-2 architecture using a text collection of around 13 GB that combines parts of the Italian Wikipedia and web texts.

- Recently, Wietse de Vries and Malvina Nissim published “As Good as New: How to Successfully Recycle English GPT-2 to Make Models for Other Languages”. In this essay published last December, they describe the adaptation of an English pre-trained GPT-2 model to Italian and Dutch, focusing on retraining the lexical embedding layer rather than fine-tuning the existing (Anglophone) lexical layer. Their article outlines a method to overcome the problems of working with language models that are commonly trained for English and typically underperform in other languages.The proposed method is supposed to help adapt existing pre-trained language models to new languages–and may be precisely the breakthrough we’ve been seeking.

Another problem we have encountered is that, in a rapidly evolving field, tutorials tend to quickly become obsolete or outdated. After our first attempt, GPT-3 arrived on the scene and many developers flocked to the new version; some of the resources, blogs, and examples that employ GPT-2 are now defunct, possibly as a consequence of their creators moving on to the newer and “better” edition. For example, we attempted to follow Pierre Guillou’s Portuguese tutorial mentioned above, but a broken link to a crucial component causes the entire process to fail–an error that, according to the github error log, has frustrated other developers and DH-meddlers. In a way, however, the exercise of using–and attempting to renovate, repurpose, retrofit, or simply revive–an outdated, now-antiquated form is, in itself, a very quixotic act, and we find ourselves inspired by that coincidence.[3]

Alas, our GPTmete Benengeli has not yet taken up his pen to rewrite the Quixote as Borges’s Pierre Menard famously did, but we believe we are inching ever closer to being able to talk to a Cervantes text generator. We have journeyed deep enough to know what we lack: additional training in Python, more research into proven methods, additional attempts at following those established methods, and, more than likely, a Zoom consultation with someone who knows more than we. Like any DH project that challenges technological Anglocentrism and stretches the limits of the researchers’ existing skill set, there are no easy solutions at hand for GPTmete Benengeli.

We will close with the final words of Cervantes’s first volume of the Quixote: “Forsi altro canterà con miglior plectio.” (“Perhaps someone else will sing with a better plectrum [pick for a musical instrument].” ) While we don’t aspire to improve on the masterpiece, we look forward to seeing how the tune sounds in the key of GPT-2.[4]

[1] The project we mention was a collaborative effort involving both authors along with Jennifer Gutman and Cameron Clark. After fine-tuning GPT-2 on a corpus of James Cain noir novels and the Billy Wilder screenplay for Double Indemnity, we prompted the transformer to produce brief film scenes. It did a splendid job of replicating the general tone of mid-century noir works, and it also followed the format and construction of a screenplay, with stage and camera directions and dialogue between characters, but it was not necessarily coherent in terms of the plot construction. Human hands were required to assemble the screenplay (this is what we mean by “co-writing”) and eventual short film.

[2] In the intervening decade between the novel’s two volumes, another author wrote the apocryphal continuation of Cervantes’ tale under the pseudonym Alonso Fernández de Avellaneda, and in Cervantes’s continuation of the narrative, not only have other characters “read about” and heard of Don Quixote and his squire, but some of the fictional figures mercilessly roast the quality of Avellaneda’s false sequel.

[3] We consider the project “quixotic” or quijotesco because the entire premise of Cervantes’s novel revolves around the protagonist’s obsession with chivalric romances, a genre falling out of fashion at the author’s time of writing.

[4] For those interested in reading the novel: Don Quixote (English), Don Quijote de la Mancha (Spanish)