SLP 5311: Stuttering

SLP 5311: Stuttering

SLP 5311: Stuttering

Cara Singer and Dillon Pruett working with

Robin Jones, Assistant Professor of Hearing & Speech Sciences

Improving student proficiency and confidence completing stuttering disfluency counts using an online module

Overview

Disfluency counts are used clinically by speech-language pathologists to diagnose and evaluate stuttering disorders. Two fundamental measures included in disfluency counts are disfluency types and disfluency frequencies (Yaruss, 1998). Evidence suggests that speech-language pathologists are both less comfortable measuring stuttering than other speech-language disorders (e.g., Cooper & Cooper, 1985; Sommers & Caruso, 1995), and exhibit low reliability on measures of stuttering frequency (Cordes & Ingham, 1994; Curlee, 1981). This study investigates whether an online module that targets disfluency types and frequencies improves student proficiency and confidence completing disfluency counts compared to business-as-usual practices.

Disfluency Types and Examples

| Stuttering-Like Disfluencies (SLDs) | Example |

| Sound/Syllable Repetitions | I w-w-w-want that |

| Whole Word Repetitions | I want want want that |

| Audible Prolongations | I wwwwwant that |

| Inaudible Prolongations | I (pause with tension) want that |

| Non-Stuttering-Like Disfluencies (NSLDs) | Examples |

| Phrase Repetitions | I want I want that |

| Interjections | I uh uh want that |

| Revisions | I want, I would like, that |

Module Development

Using backwards design, we identified our primary learning objectives prior to creating the assessment tools and online module.

Learning Objectives

- Classify stuttering-like disfluencies (SLDs) and non-stuttering like disfluencies (NSLDs)

- Identify SLDs and NSLDs in a speech sample

- Analyze a speech sample using a 300-word disfluency count and calculate measures of disfluency

- Describe the results of a speech sample in patient/parent-friendly terms

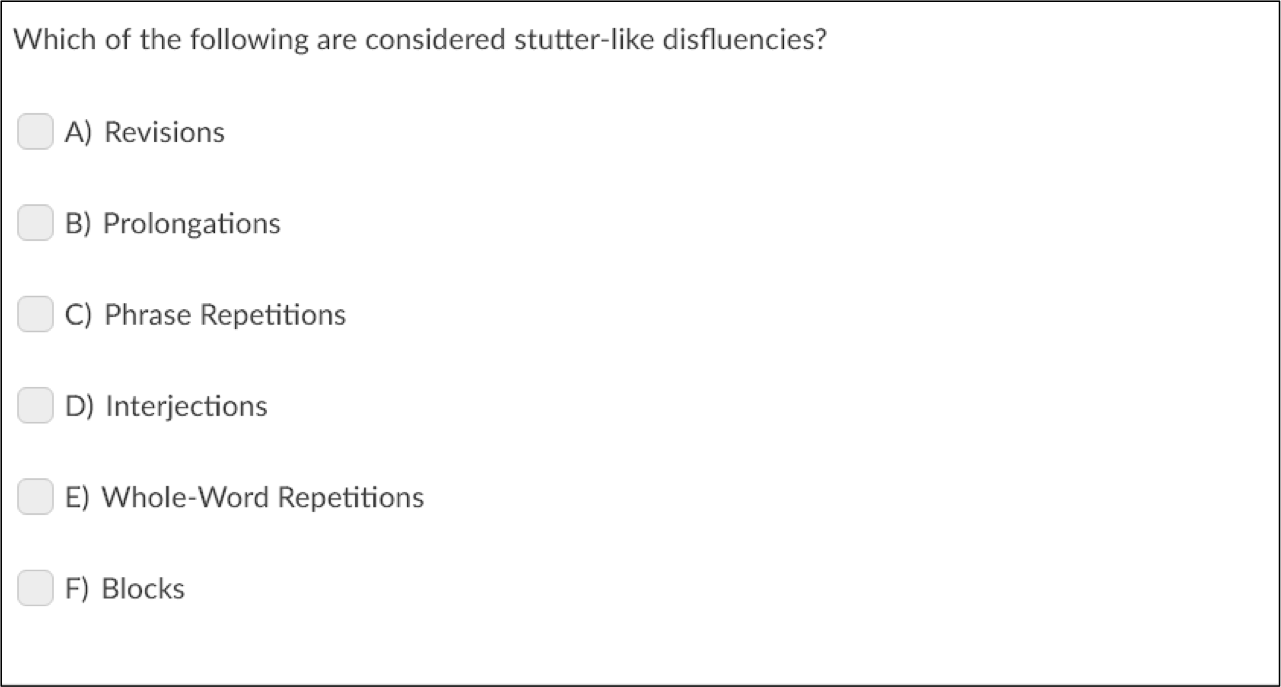

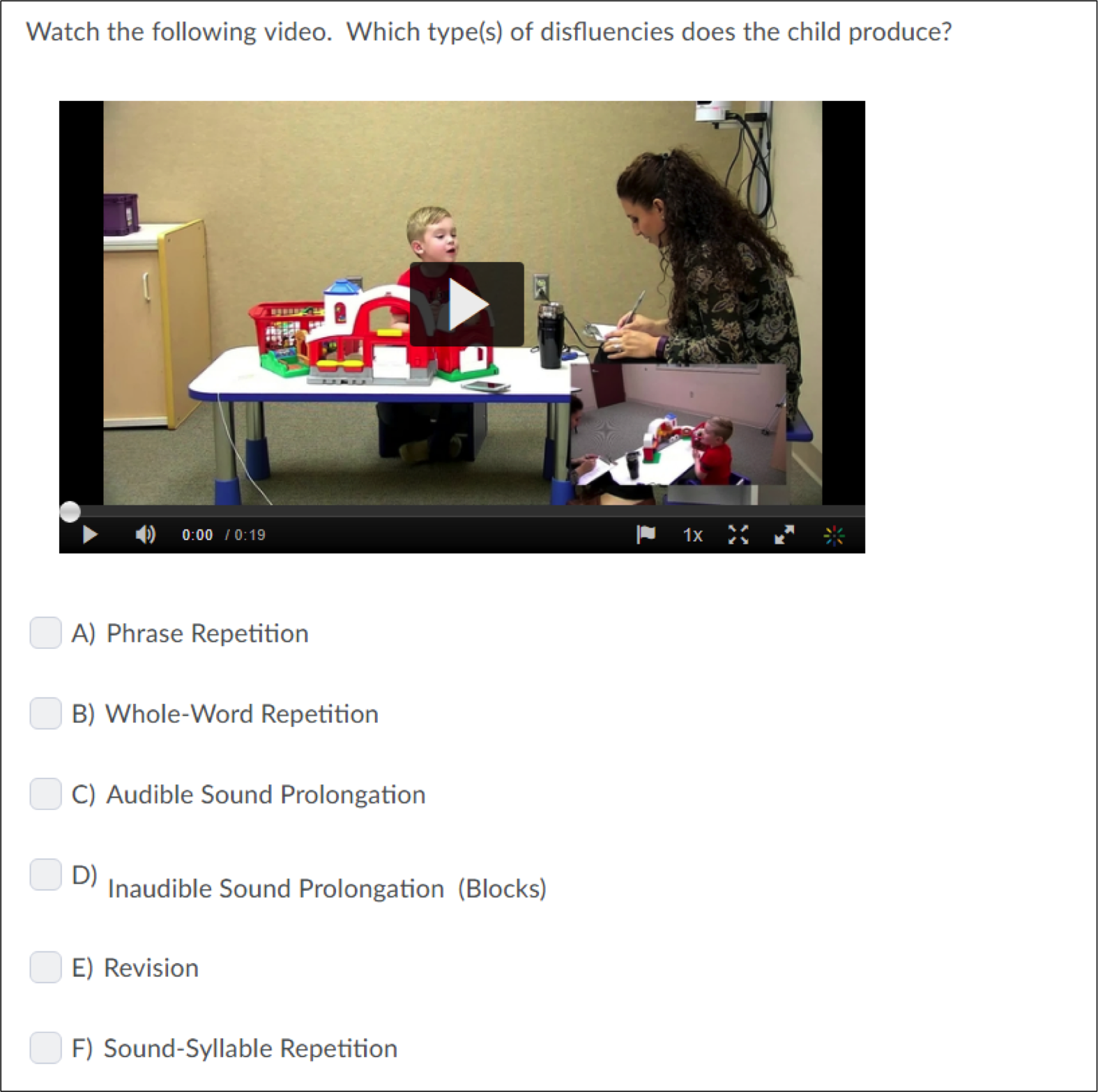

Assessment and Survey

The 5-question assessment was developed on BrightSpace to measure student progress on the learning objectives by comparing performance on the first day of class (pre-instruction) to performance 9 weeks later (post instruction). Students were given 11 minutes to complete the assessment.

Some questions are knowledge-based while others require students to view a video and analyze disfluencies. Examples of both question types are illustrated below:

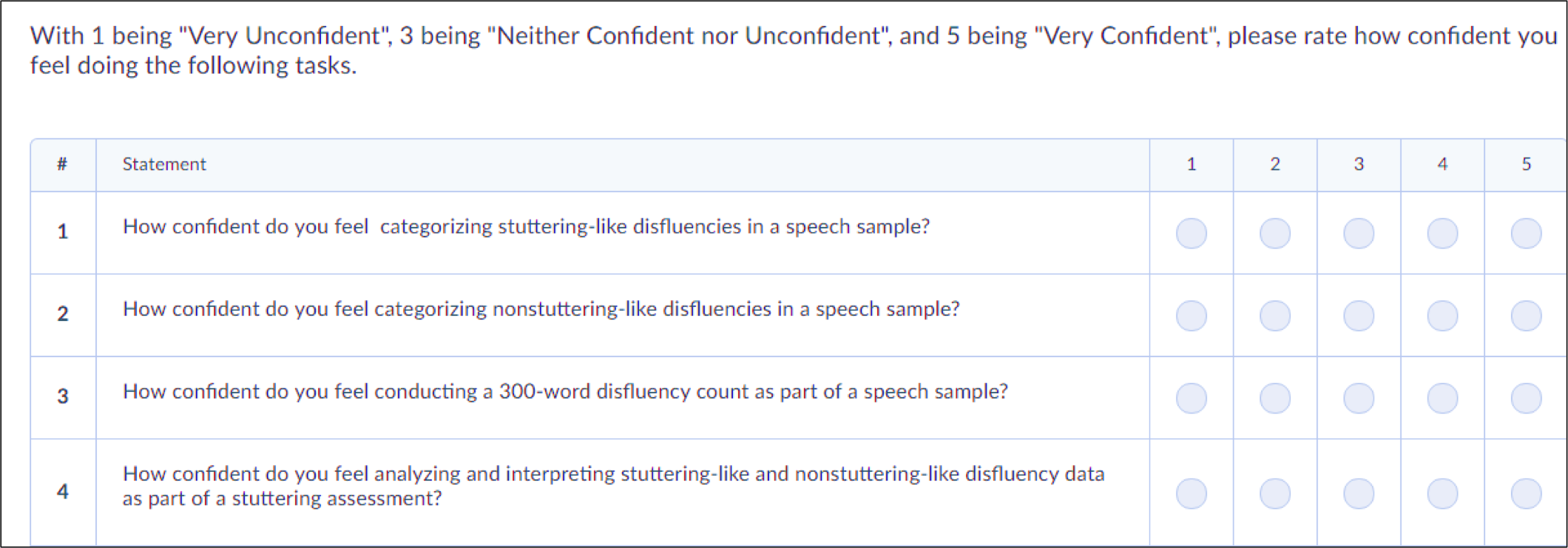

Additionally, a survey was created to collect student demographic information, student-reported confidence post-instruction, and student feedback. Demographic information included general information (e,.g, age, gender, and race) and stuttering-specific information (e.g., number of classes previously taken that focused on stuttering, number of observation hours in stuttering treatment, etc). Self-reported confidence questions included learning objectives (as seen below) and stuttering assessment measures discussed in class, but not included in the module (e.g., Sound Prolongaton Index, Stuttering Severity Instrument, KiddyCAT, etc).

Control Intervention

A control sample of masters speech-language pathology students (n = 14) was was used to determine student profiency and confidence following “business-as-usual” instruction. Instruction consisted of 1-hour in-class labs during the first 8 weeks of class and the completion of five 300-word disfluency count speech samples as lab homework.

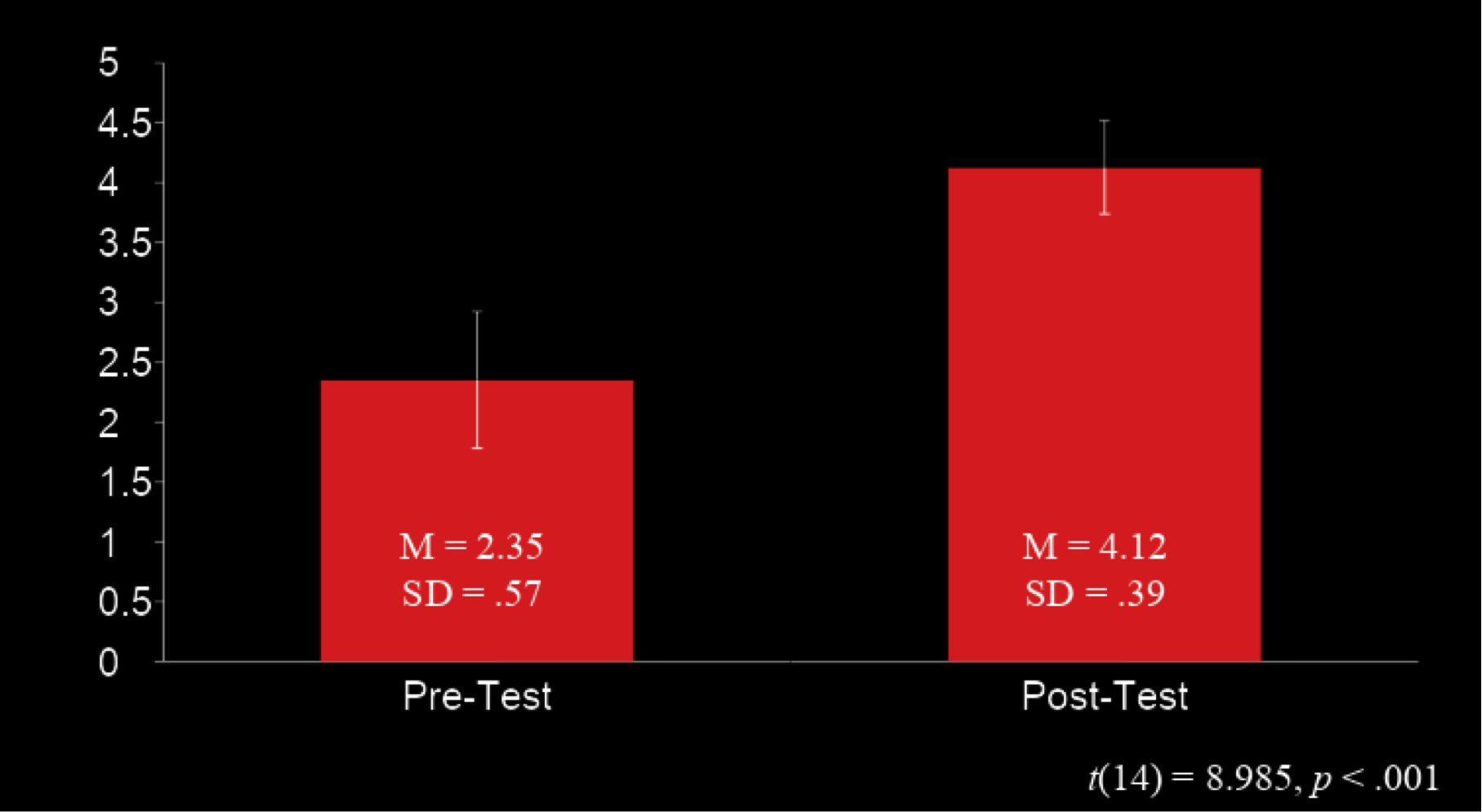

Results

Results from the asssessment indicated that business-as-usual instruction resulted in improved profieciency, but that there was still room for improvement.

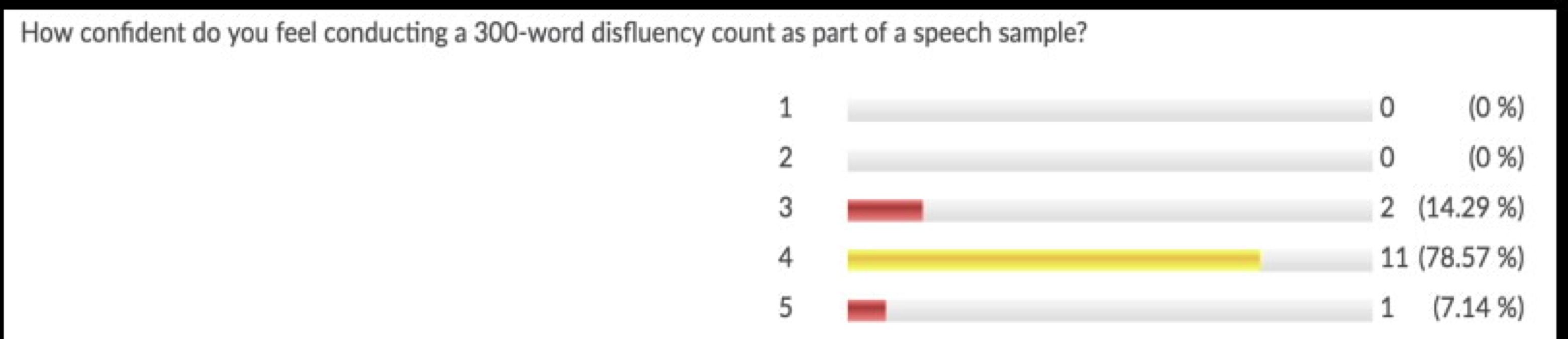

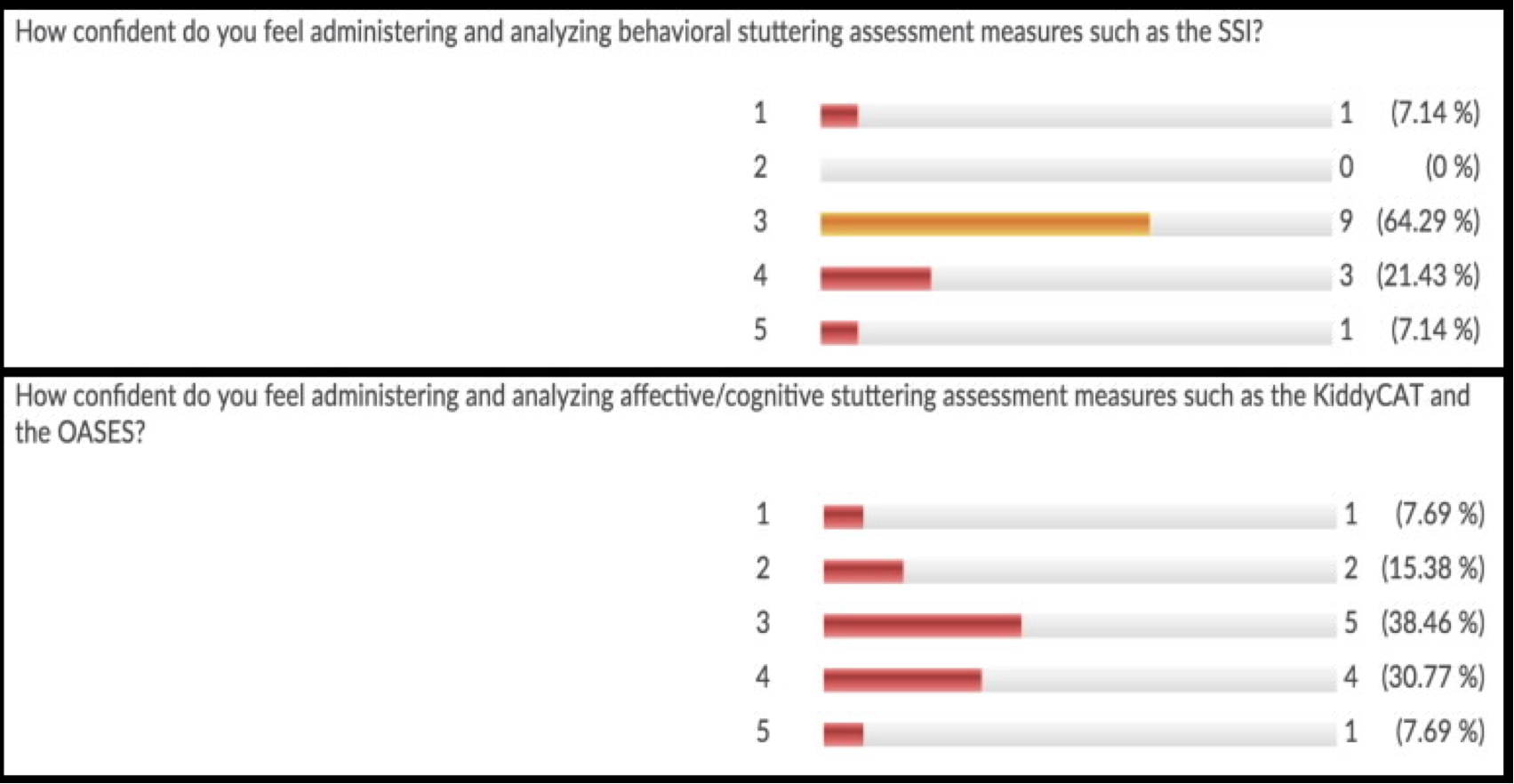

Results from the survey indicated that the control sample, as group, felt confident administering a 300-word disfluency count (one of the amin goals of the future online module), but did not feel as confident administering the Stuttering Severity Instrument and other affective/cognitive stuttering assesssments.

Student feedback included the desire for “more guided practice in doing a disfluency count prior to independently watching the video” and “…a speech/behavioral sample…where the narrator explained what he/she observed and how he/she would code that.”

A poster describing their results can be found here.

Future Directions

Based on results from the control sample, we believe that the proposed module will be a useful tool to further promote student proficiency and confidence completing stuttering disfluency counts as well as other measures as part of a comprehensive stuttering assessment.

References

Cooper, E., & Cooper, C.S. (1985). Clinician attitudes towards stuttering: A decade of change (1973–1983). Journal of Fluency Disorders, 10, 19–33.

Cordes, A.K., & Ingham, R.J. (1994). The reliability of observational data: II. Issues in the identification and measurement of stuttering events. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 37, 279–294.

Curlee, R.F. (1981). Observer agreement on disfluency and stuttering. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 24, 595–699.

Sommers, R. K., & Caruso, A. J. (1995). Inservice training in speech-language pathology: Are we meeting the needs for fluency training? American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 4(3), 22–28.

Yaruss, J. S. (1998). Real-time analysis of speech fluency: Procedures and reliability training. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 7(2), 25-37.

photo credit