Unique three-stage spine surgery saves woman’s life

Judy Kerns was facing a one-of-a-kind problem. Here’s how she put it: her head had fallen off her neck.

You would expect a medical professional to put this in more scientific terms, but Matthew McGirt, M.D., uses pretty much the same words as his patient: “Her head had literally fallen off her spine, and it was a miracle she wasn’t paralyzed,” said the assistant professor of Neurosurgery.

Just four weeks into his faculty career at Vanderbilt, McGirt conceived and executed a surgery that had never been done before, taking Kerns from being bent over and near death, to an upright posture.

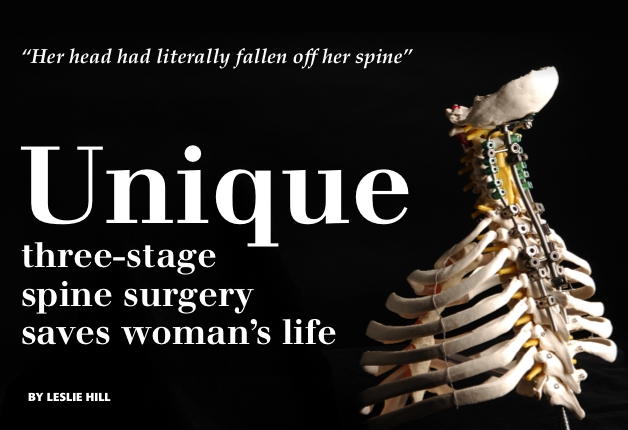

“Really the only thing [not rebuilt in her neck] is her spinal cord, the important arteries that go up to the brain and the nerves that run out into the arms,” McGirt said. “We took out almost all of the bone and rebuilt her structural neck with metal and titanium.”

Damage from a car wreck

It started in October 2009 with a simple car accident in Harriman, Tenn., her hometown. While Kerns was sitting at a red light, she was rear-ended and knocked into the car in front of her. Then another car caused a second impact.

“It felt like a house had come through the car,” she said. “My neck snapped and I felt paralyzed. I slowly started getting my feeling back but was in intense pain.”

Her physician diagnosed whiplash, but the pain never got better. Kerns wasn’t comfortable standing, sitting or lying down.

In January 2010, she was referred to a spine specialist who did an MRI.

“It showed that my spine was falling over. The doctor said he didn’t see how I was even walking,” Kerns recalled.

Progressive degeneration was causing the bones in her neck to break down, and the car accident had accelerated the deterioration. Doctors in nearby Knoxville performed two surgeries, but nothing improved the pain. Kerns was simply given a neck brace to wear.

She took the brace off one day for a bath, and all at once her head fell over onto her chest and she couldn’t lift it up again.

“I tried to put on my neck brace and force it back up but it hurt so bad and I would go numb in my arms and legs,” Kerns said.

One problem led to another. Her jaw began to rub on her clavicle, and what started as a small sore eventually grew into an infected ulcer that wouldn’t heal. A wound care specialist noticed that the skin had been worn down to the bone.

“I really thought that would kill me. I thought my chin would eat through my throat,” Kerns said. “I felt like I was slowly dying. I couldn’t eat or talk, and I’ve got to talk. I’m a talker.”

Kerns had to eat by breaking food into tiny pieces and pushing it between her teeth, and the 50-year-old said she would look like a baby with food all over her face. Her weight dropped dramatically to 98 pounds.

Custom implant needed

Desperate to find help, a friend drove Kerns the 150 miles to the Vanderbilt University Medical Center emergency room.

“I got a phone call from the ER but little did I know the magnitude of her case,” McGirt said. “She was on her way to dying in the next few months and was desperate for help.”

Even though McGirt had never attempted to rebuild someone’s entire cervical spine, he knew he had to do something. But McGirt wasn’t even sure Kerns would survive surgery. Before he could rebuild her neck, he had to rebuild her health, and healing the ulcer was paramount.

“We knew it would be a one- to two-month process to create room between her head and neck to close the wound,” McGirt said. “She also needed nutrition to put on weight and antibiotics to fight the infection.”

To slowly pull her head off her chest, Kerns had pins placed in her skull and weights were hung to pull her head back over time. Once enough space was created, her head was held up in a rigid halo vest. It was two weeks before McGirt felt confident that Kerns could survive surgery.

Because the traction process was so painful, Kerns was kept heavily sedated and only remembers snippets of her time in the hospital.

While Kerns was in traction, McGirt worked with an orthopaedic device manufacturer to design a custom implant for Kerns’ neck.

“We had many planning sessions leading up to the surgery, looking at CT scans and developing models. Nothing existed for this, so we had to make a completely new design,” McGirt said.

McGirt work with the company to create a cage to sit under her head to replace the vertebral bodies and discs and serve as a structural foundation. There are also two rods in the back to screw into the chest and base of the skull and a third supplementary rod to hold the head off the chest. The spinal cord and vital arteries to the brain would run between the cage and rods.

With usual spine implants, the remaining bone fuses with the metal, which strengthens the construction. Because all the bone had been removed, there was no chance this would happen, so it was crucial that Kerns’ implant be strong and durable.

“We knew she would need to live 30 years relying on the hardware,” McGirt said.

Extraordinary imagination

Reid Thompson, M.D., chair of the Department of Neurological Surgery, praised McGirt for his innovation.

“It was extraordinary just to imagine how to do the surgery,” he said. “Most people would wonder how it was possible that someone only a few months out of their residency could pull off an operation that had never been done before, but I knew his skill set and had nothing but confidence.”

McGirt planned to do the surgery in three stages. He knew he had a solid plan, but one worry was always looming—the risk of paralysis. He was astounded Kerns wasn’t already paralyzed and knew the slightest mistake could bring the worst consequences.

“After each of the stages, we never knew until we woke her up and got her to move whether or not her spinal cord tolerated it. Each day was a victory. Every night when we finished, we all waited to see her wiggle her toes and move her fingers and determine that we had made it through one-third of the battle.”

On the first day, McGirt opened the back of Kerns’ neck to remove her bone and the metal from previous surgeries and implant screws. The second day, he did the same process in the front, removing the old bone and hardware and implanting the metal cage. James Netterville, M.D., professor of Otolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery, helped with the complex navigation of her old scars.

On the final day, the rods were implanted and the final screws were secured. Because this placement would determine her posture for the rest of her life, McGirt had to make the alignment perfect.

“She can bend at the waist and rotate at the waist, but as far as her head goes, she can’t nod or rotate. We had to make sure how her head was sitting and where her eyes would look was in a position that was functional.”

The muscles in her neck were also diseased and needed to be removed. Because Kerns had lost so much weight, there was concern that all the metal would erode her spine and skin without muscle to protect it. With the help of Wesley Thayer, M.D., Ph.D., assistant professor of Plastic Surgery, McGirt swung part of the latissimus muscle in her back up to her neck.

“Beauty mark”

Kerns was extubated 24 hours after her final surgery and was up walking two days later.

“She was cheerful and happy. She was scared she would be paralyzed and when it was clear to her that she was not, her emotions and actions said it all. And we were all very happy for her,” McGirt said. “It was my fourth week as an independent surgeon and it may be one of the most rewarding cases of my career.”

Kerns doesn’t remember much of this moment, just relief that her head was up and she wasn’t paralyzed.

When Kerns returned for follow-up recently at the Vanderbilt Comprehensive Spine Center, McGirt was pleased with her progress.

“We’ve reached the five- or six-month period where it would be clear if this fix was durable and effective, and the X-rays show this is a solid construct. That’s the no. 1 issue with doing something novel,” he said. “All her major symptoms are gone. She can swallow and function in her daily activities. From a spinal perspective, she couldn’t be doing any better.”

Kerns, with her enormous smile and perfectly straight posture, is quick to show off her “beauty mark,” the enormous diamond-shaped scar running down her neck.

Having a rigid neck has taken some getting used to. Simple things, like looking into high kitchen cabinets, are no longer possible. She can’t climb anything because a fall could paralyze or kill her.

“It is hard to get used to not moving my neck and I get aggravated,” Kerns said. “I can’t do what I used to do, but I’m better. I’m alive. I definitely have no complaints.”

April 17th, 2011

I always knew we have some great physicians here at vandy. But after reading this storynthis defintely validates that our physicians go over and beyond to help their patients. nDr McGirt you are the best.

April 21st, 2011

I was priviliged enough to work beside and for this brillaint surgeon, and what he did for Judy was undoubtedly an amazing gift that few will ever possess.

April 21st, 2011

Wow! Imagine the bill the other driver’s insurance company is going to get. Yikes! This is amazing and a testament to our doctors here. Bravo!

September 22nd, 2011

They are absolutely abundant surgeonsu00a0.what he did for Judy was assuredly an amazing allowance that few will anytime possess After account this adventure this definitely validates that our physicians go over and above to advice their patients.